|

“BOTTLES AND KEGS” “BOTTLES AND KEGS”

A HISTORY OF SODA AND BEER BOTTLING

IN

A SOUTHERN SEAPORT TOWN

DURING

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

by

Fred C. Cook

All Rights Reserved © 2012

|

i

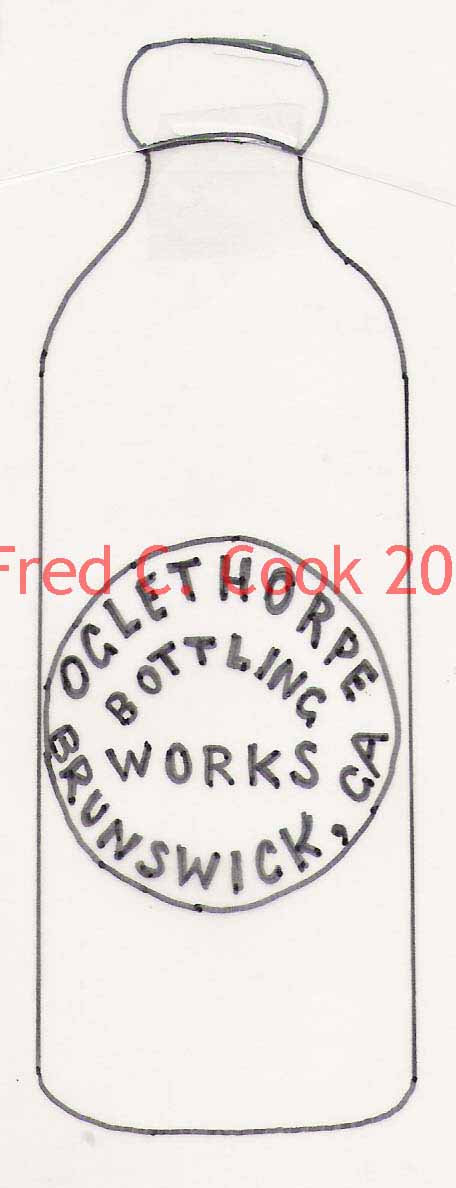

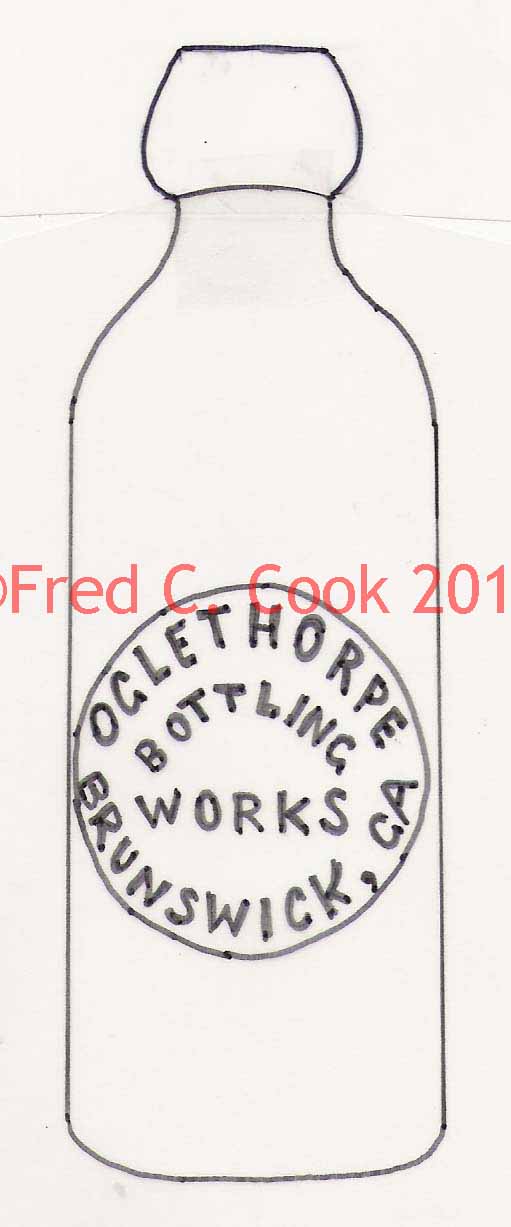

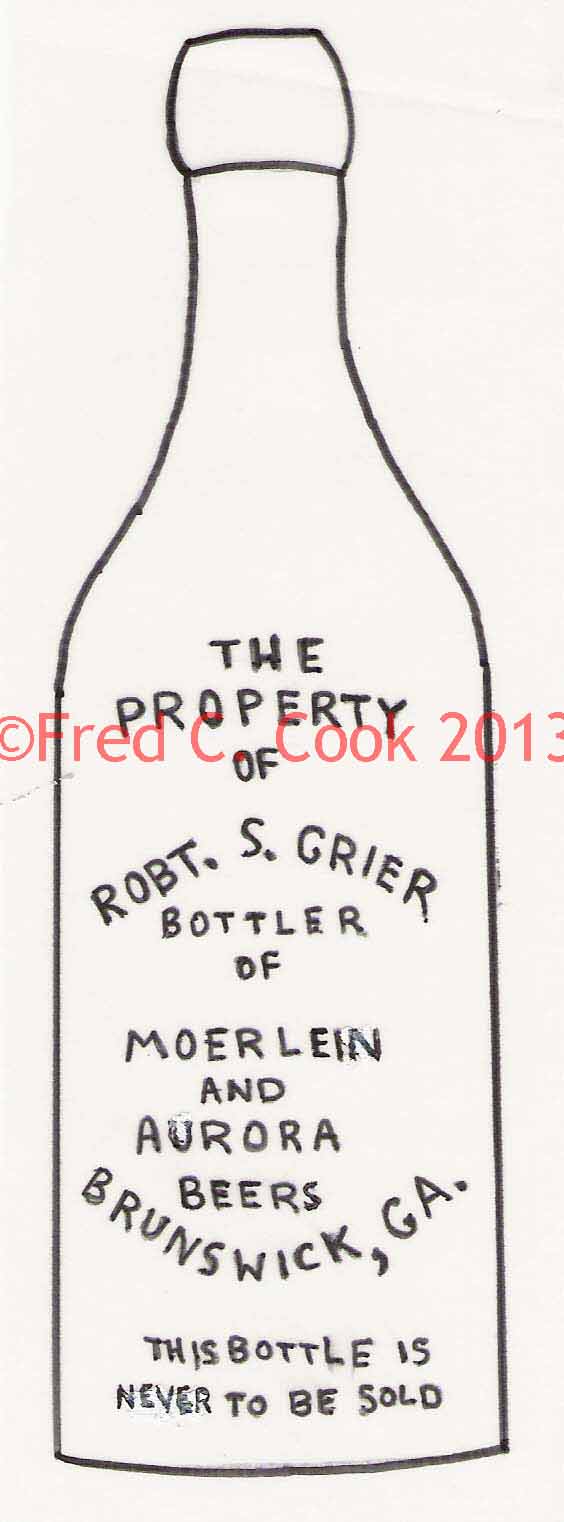

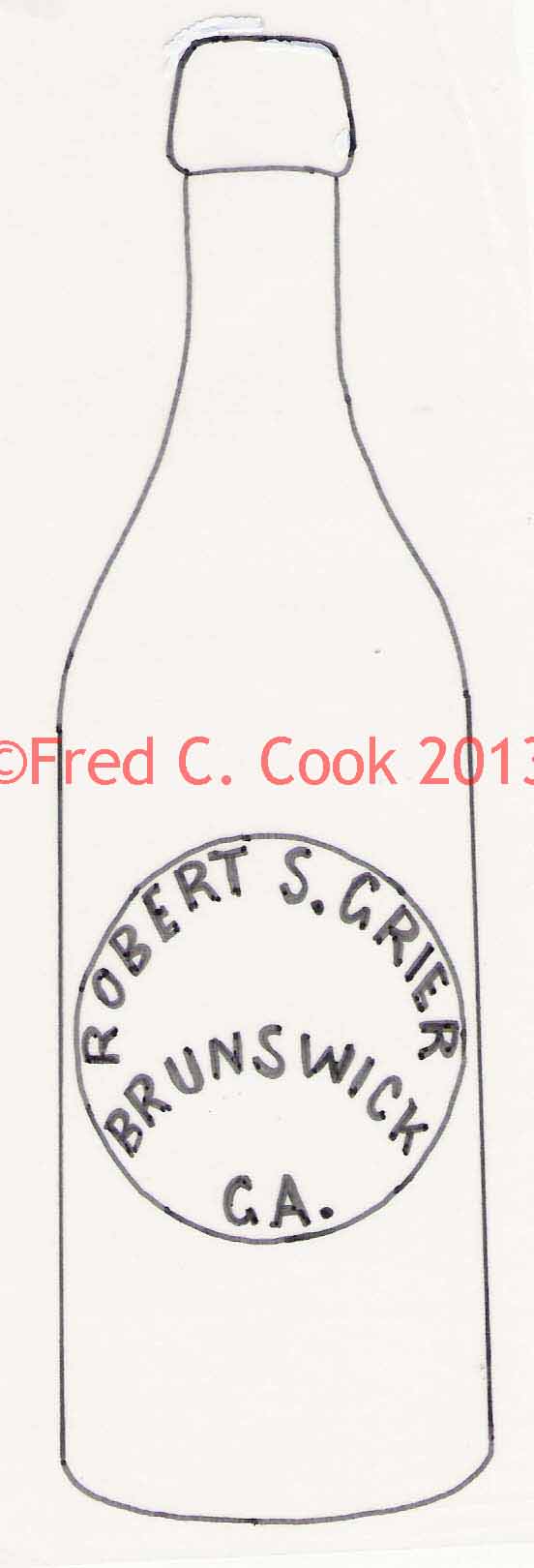

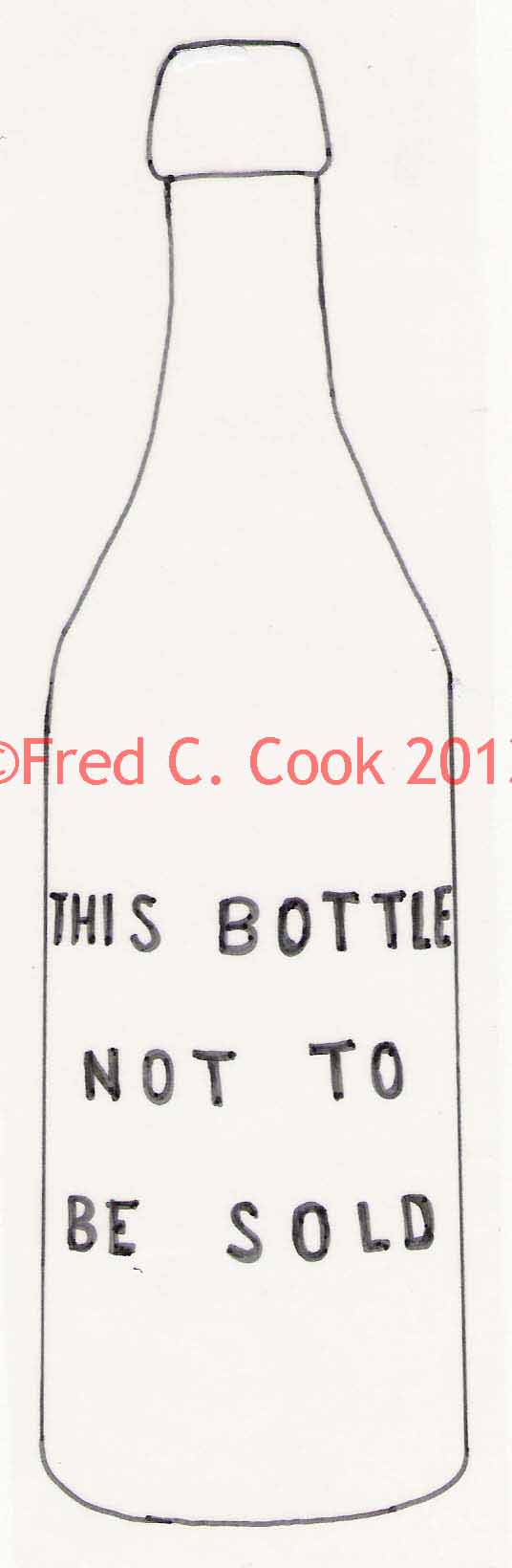

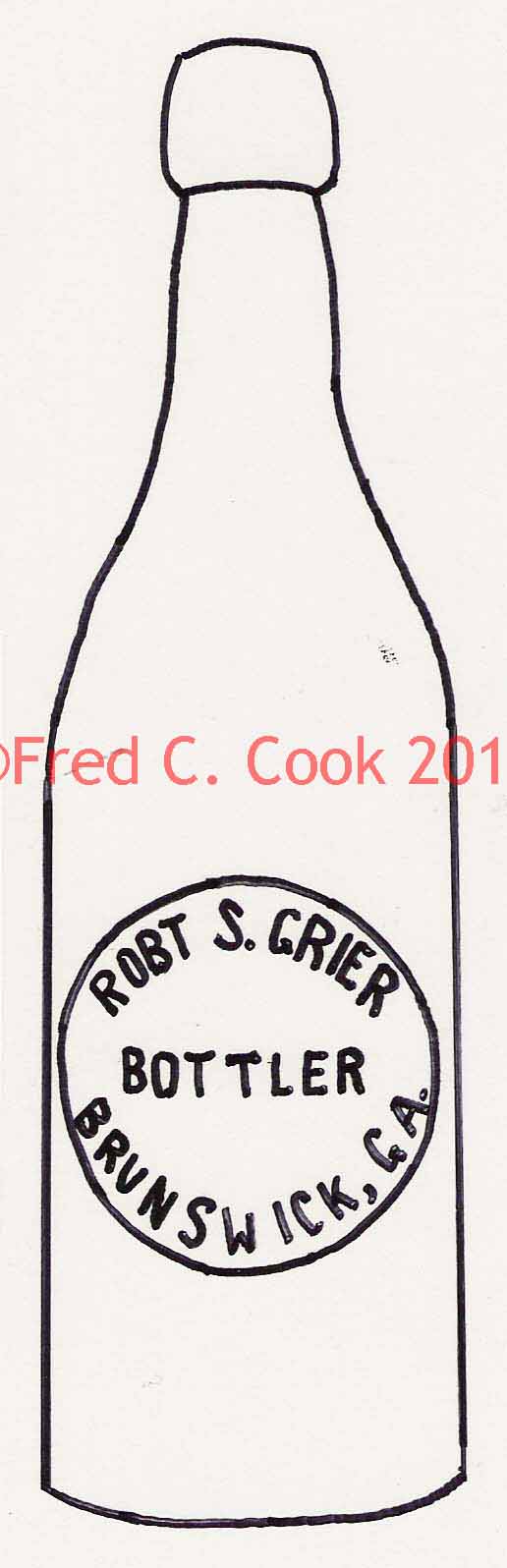

Strawberry Soda water and draft beer were two of

the beverages bottled in Brunswick, Georgia in the nineteenth

century. Shown above are the original bottles used by

Oglethorpe Bottling Works and Robert S. Grier in the

1880’s. The contents are modern.

i |

|

ii

FORWARD

This book was written for those people who share my interest in

small scale nineteenth century soda and beer bottling. Inspired by

this subject, I gathered information from historic maps, newspapers,

city directories, U. S. Census records, U. S. Patents and court

house documents in order to recreate what beverage bottling was like

in Brunswick, Georgia, a small southern seaport. The few excavations

conducted were in connection with the archaeology classes I taught

at McIntosh County Academy in 1998 and 1999. The students

participated in archaeological field work, analyzed the artifacts

and presented their interpretations in triptych public displays.

This book focuses on what I discovered about those early bottler’s

lives and their businesses. Within its more than sixty pages of

content, this book features twenty-one color photographs,

twenty-seven illustrations, twelve historic maps and forty-one line

drawings that depict all known types of soda and beer bottles

embossed with the name of a Brunswick bottler. A bottle rarity guide

is also provided in an appendix.

In the nineteenth century some of Georgia’s cities and towns, such

as Brunswick, had businesses that formulated, mixed and bottled

their own flavors of soda water. The technology that was available

at the time allowed this beverage to be manufactured and bottled on

a small scale. Often, the back room in a grocery store provided

sufficient space for the necessary soda equipment. My maternal

grandmother told me tales of bottling soda at her father’s general

store in West Point, Georgia. Unlike beer that was sterilized by

heat during the brewing process, soda water was sometimes made with

poor quality shallow well water. Furthermore, microbial

contamination could occur during production, bottling and even

storage in bottles whose design allowed dust, dirt and pest filth to

collect in their necks. However crude its method of production may

have been, soda water bottling was a thriving business in Brunswick

by the 1880s.

While soda bottling was getting started in Brunswick, some of the

local saloon and liquor merchants were purchasing beer by the keg

for retail distribution. Most of the beer came from distant

Midwestern brewers, who delivered it directly to Brunswick in

refrigerated rail road cars and, for a few short years, a local

brewery. These kegs were tapped in the merchant’s place of business,

and the contents were sold by the mug or bottled for distribution

throughout the community. These businesses were identified by the

glass bottles that bear the proprietors’ names, Sanborn maps and

Brunswick Directories.

During this same period of time, there were over two thousand

breweries in the United States. However, the largest Midwestern

breweries had begun to edge many of their small competitors out of

the market. Companies such as Pabst, Anheuser Busch and Schlitz used

methods that were the brewer’s equivalent of mass-production.

Furthermore, the newly implemented process of pasteurization helped

extend the shelf life of bottled beer, making storage and

transportation to distant markets feasible. These large breweries

were able to produce and market palatable beers that were consistent

in quality. In contrast to their Midwestern counterparts, many of

the small scale southern breweries used techniques that favored

using numerous small batches in order to achieve the

ii |

|

iii

volume of production they desired. Needless to

say, their beers were far less uniform than those produced by their

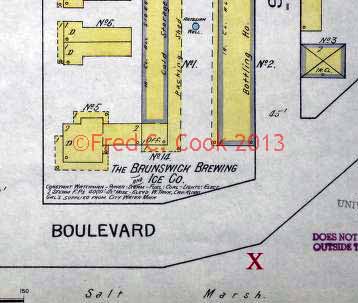

Midwestern competitors. For a brief period of time, Brunswick was

the home of such a brewery. Its advertised annual 50,000 barrel

production, a volume they probably never achieved, was only

one-twentieth of the capacity of the contemporary Pabst brewery in

Milwaukee. A detailed historic map and a document found in the Glynn

County Courthouse provided a wealth of information about this small

town brewery.

Today there is a growing interest in embossed nineteenth century

soda and beer bottles. The main reason for this interest is the fact

that these bottles were manufactured by one of the last American

industries to produce hand crafted items employing artisan-like

skills. Furthermore, in the vast majority of cases, glass bottles

are the only surviving tangible remains of the businesses they

represented.

The viewer should be aware that the CD version of this book provides

two important features. The first is the “go to” button under

“edit.” This provides an easy way to navigate from one page to

another. The second feature is the “zoom” window in the tool bar.

This allows photographs and illustrations to be viewed at higher

magnification. All of these should be viewed at 150-200%.

The primary sources of information used for this book were:

Newspapers:

Brunswick Daily Advertiser and Appeal (March, 1875-November,

1889)

Brunswick Times Advertiser (January, 1894-November, 1896)

Brunswick Call (May, 1896-March, 1901)

City Directories:

Brunswick City Directory (1890)

Howard’s Directory of Brunswick, Darien, St Simon and St. Mary’s

(1892)

Vance’s Brunswick and St Simon Consolidated Business and

Partnership Directory (1896)

Due to the length of the directory titles they are referenced in the

text with the generic term “Brunswick city directory.”

Maps:

Brunswick, Georgia Sanborn Map and Publishing Co. April, 1885

Brunswick, Georgia Sanborn Map & Publishing Co. Limited May, 1889

Brunswick, Georgia Glynn Co. Sanborn-Perris Map Co. Limited April,

1893

Brunswick, Georgia Glynn Co. Sanborn-Perris map Co. Limited July,

1898

Columbus, Georgia Sanborn Map & Publishing Co. February, 1885

Columbus, Georgia and Environs Sanborn-Perris Map Co. Limited Sept

1895

Due to the length of the map titles they are referenced in the text

with the generic term “Sanborn map.”

F.C.C. 2012

iii |

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FRONTISPIECE: Oglethorpe Bottling Works and

Robert S. Grier

Bottles……………………………………..............................................………………………………..

ii

FORWARD.…………………………..............................................……………………………………

iii

CHAPTER ONE: Brunswick, Georgia, Early History

and the Roots of Its Bottling Industry..............1

CHAPTER TWO: The History and Technology of Soda

Water and Beer.............................................4

Part

One-Soda....................................................................................

4

Part Two- Beer……………………………………………………...

8

Part Three- Bottles………………………………………………….

10

CHAPTER THREE: Brunswick’s Nineteenth Century

Soda Bottlers...................................................16

Brunswick Bottling Works…………………………………………

16

Oglethorpe Bottling Works…………………………………………

16

Brunswick Brewing & Ice Company………………………………..

20

T. B. Ferguson……………………………………………………..

21

C. O. Marlin & Company…………………………………………..

31

William B. Gunby…………………………………………………...

32

Acme Bottling Works……………………………………………….

32

L. Markowitz……………………………………………………….

32

CHAPTER FOUR: Brunswick’s Early Twentieth Century

Soda Bottlers..............................................36

Louis Ludwig……………………………………………………….

36

Cline & Ludwig…………………………………………………….

36

Brunswick Bottling & Manufacturing Company…………………......

37

Brunswick Coca-Cola Company………………………………...…

38

CHAPTER FIVE: Brunswick’s Nineteenth Century Beer

Bottlers….....................................................39

Benjamin Hirsch……………………………………………………..

39

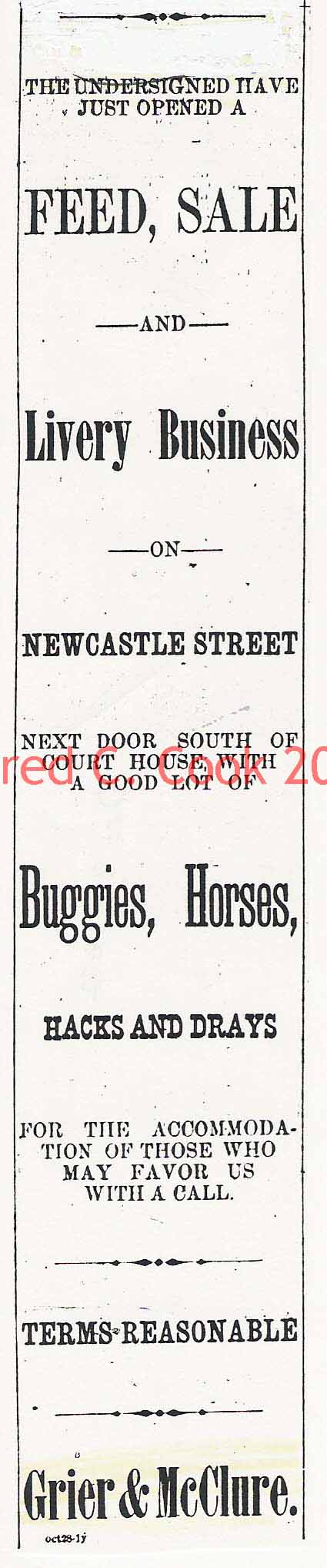

Robert S. Grier………………………………………………………

43

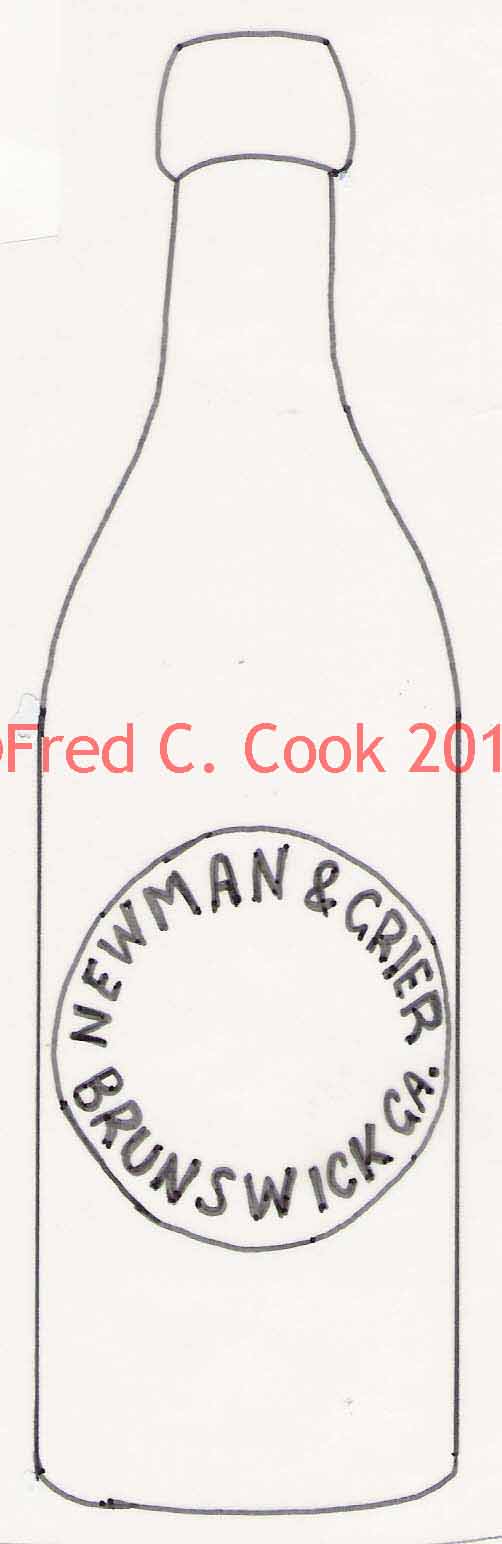

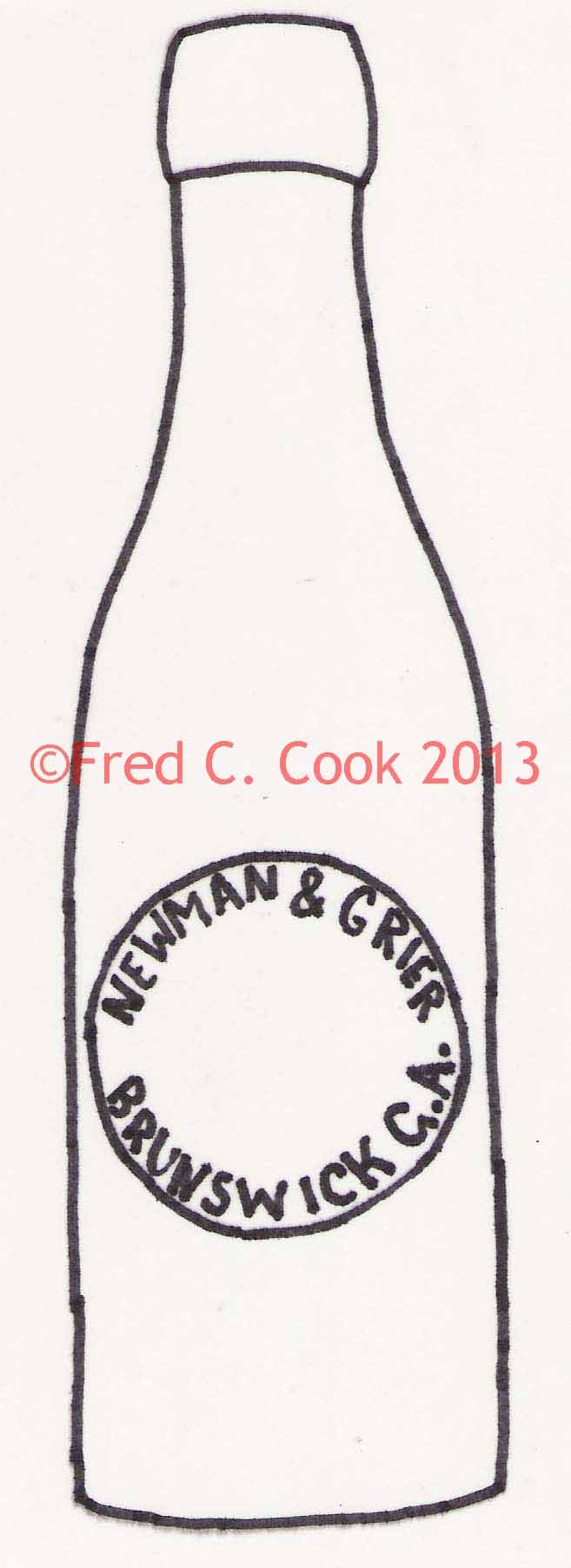

Newman & Grier…………………………………………………….

46

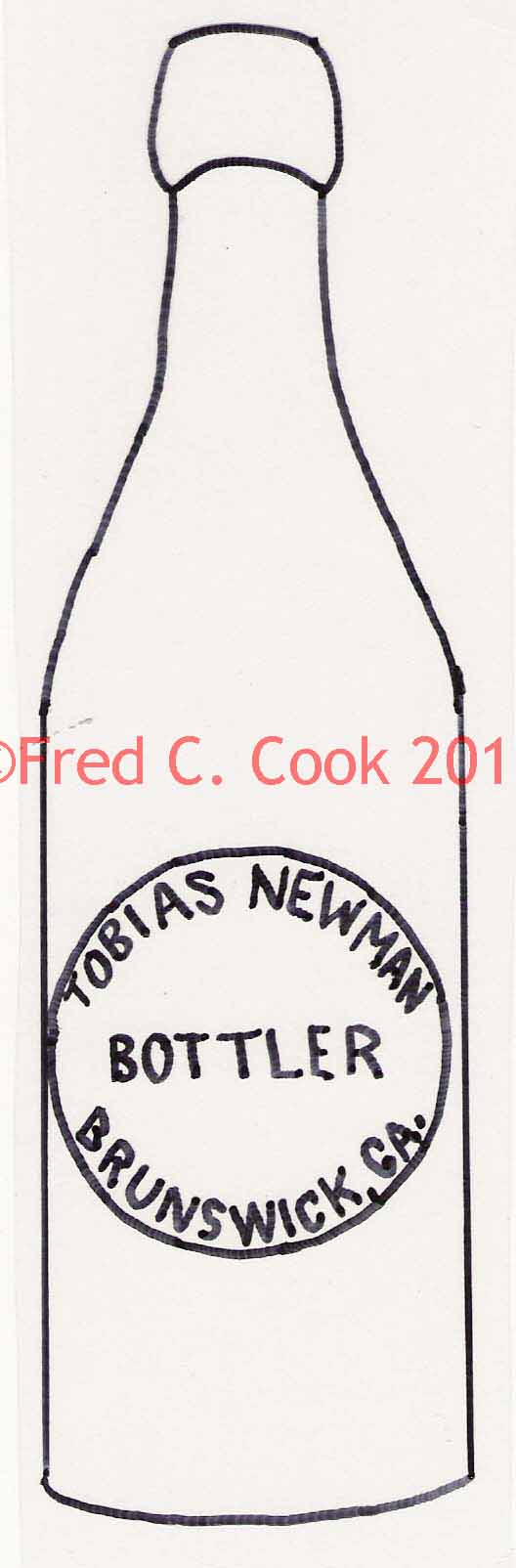

Tobias Newman……………………………………………………...

47

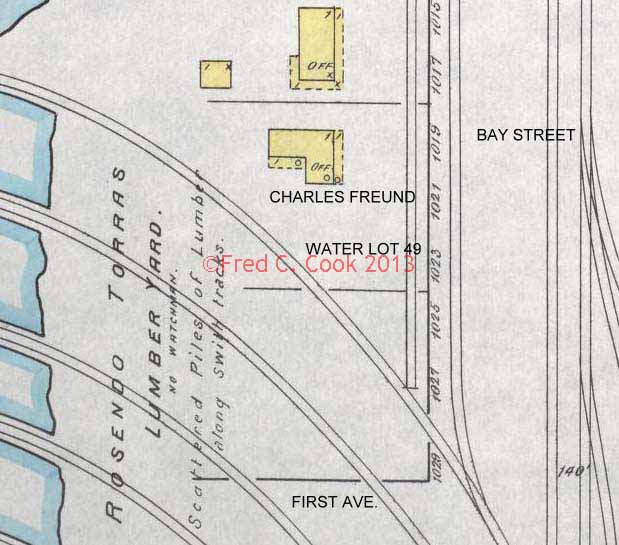

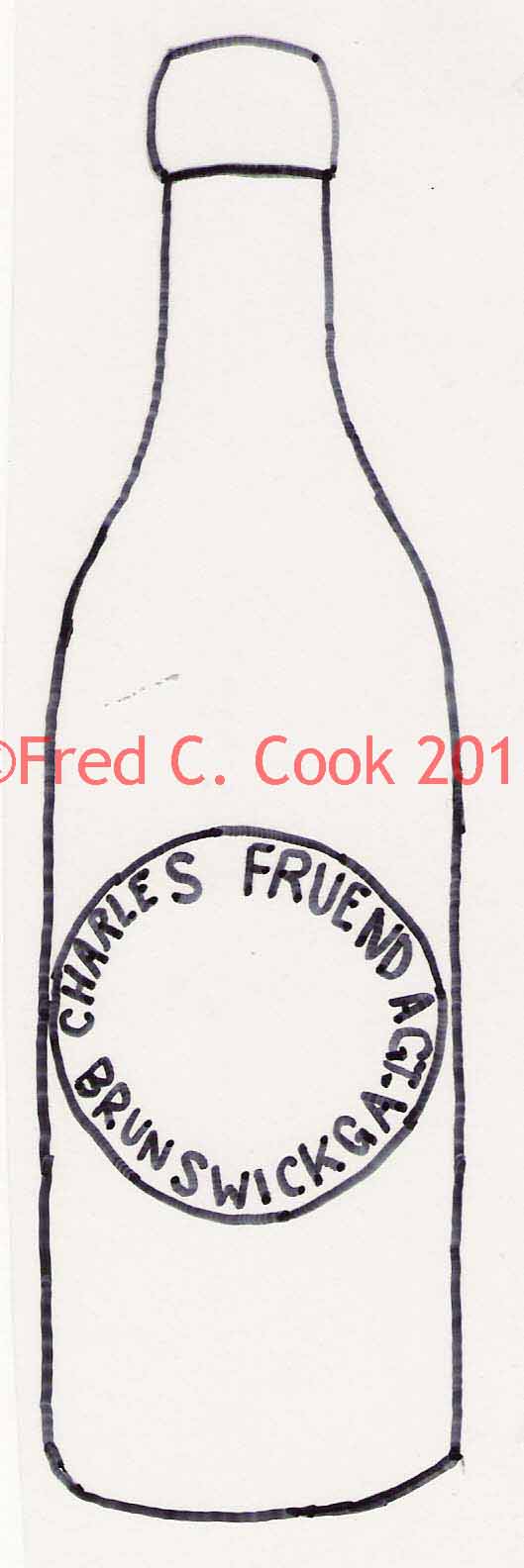

Charles Freund Agt…………………………………………………..

53

Brunswick Brewing & Ice Company……………………………….…

54

Appendix 1- Bottle Rarity

Guide……………...............................................……………………………

65

iv |

|

pg. 1

CHAPTER ONE—BRUNSWICK,

GEORGIA, EARLY HISTORY AND THE ROOTS OF ITS BOTTLING INDUSTRY

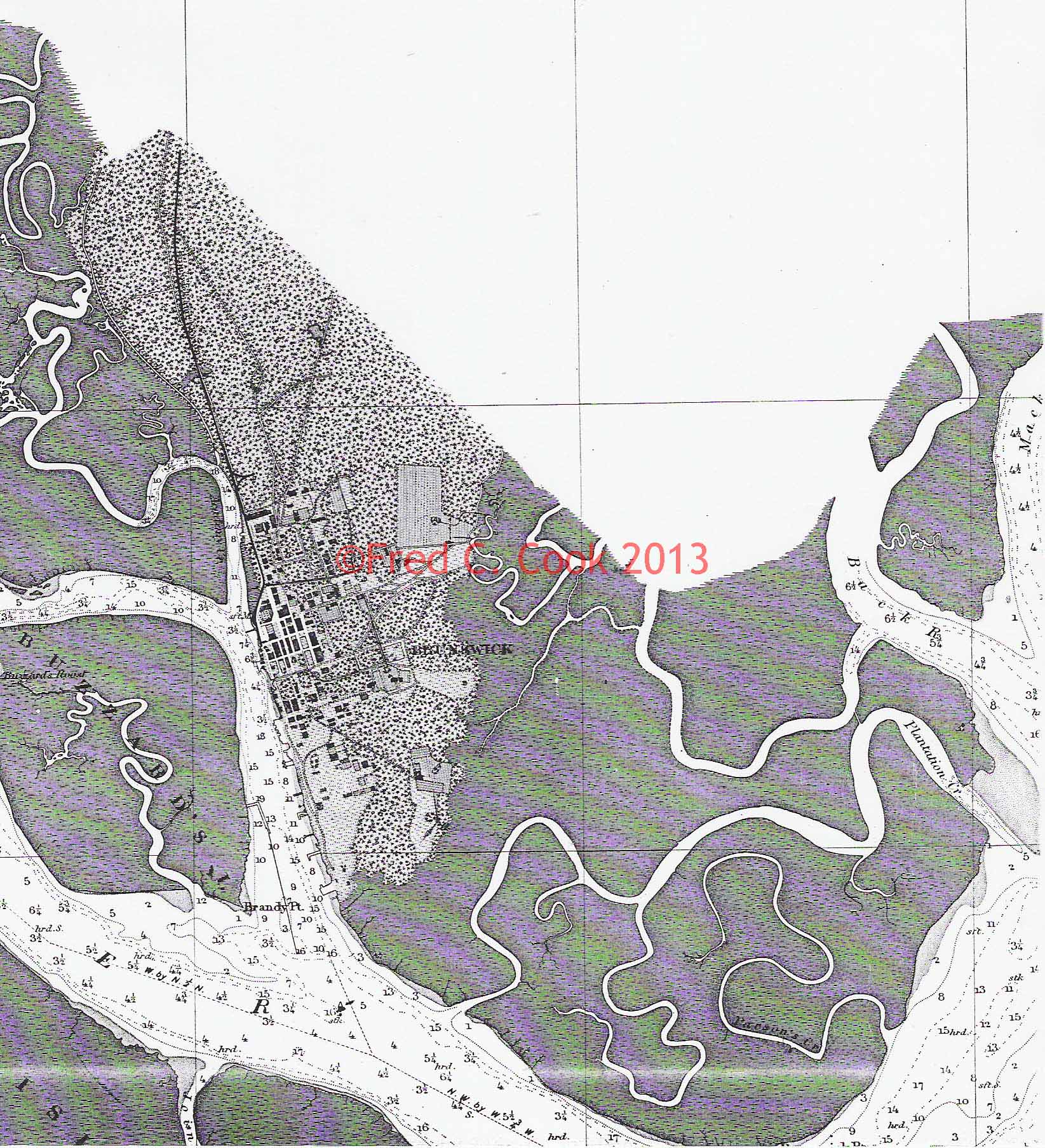

The harbor town of Brunswick, Georgia in 1857.

The town of Brunswick was established in the

eighteenth century as a small sea port on the southern Georgia

Coast. Its location on the western side of a flat forested

peninsula provided its harbored vessels with excellent protection

from storms. In its recorded history, Brunswick has

experienced only one hurricane causing major damage.

pg. 1 |

|

pg. 2

The Brunswick peninsula was first inhabited by prehistoric Indians,

who occupied the area intermittently from about 8,000 B. C. until

the sixteenth century. The Native Americans were attracted to

the peninsula by the prolific acorn crops of its Live Oak forests

and ideal access to Turtle River and its tributaries. These

waters provided, in abundance, the fish, oysters and clams that were

also important to the Indians’ diet. Archaeological surveys of

the Brunswick peninsula indicate that the main Indian occupation

occurred there between 600 and 1400 A. D. By the middle 1500s,

the Native Americans of coastal Georgia were suffering from European

born diseases and subjugation. Indians in the Brunswick area

responded to these conditions by withdrawing to mission sites on

Cumberland Island. There is no evidence to indicate that the

Brunswick peninsula was occupied for the next two hundred years.

Then, after almost two centuries of abandonment, the area was

repopulated in the 1730s by the famous settler Mark Carr

and his family. Carr, who had his principal plantation

on the Brunswick peninsula, helped General James

Oglethorpe fend off Spanish attacks launched from northeast

Florida.

The town of Brunswick was formally founded in 1771 and it grew

slowly for the next one half century. By the second quarter of

the nineteenth century, Brunswick was enjoying a period of

prosperity. However, the economic depression of 1839

terminated its growth for over a decade. About 1850 another

period of economic prosperity began. This new period of

economic success was based on shipping commerce, which continued to

increase for another decade. Brunswick became more populous

during this time and it was incorporated in 1856. James

T. Lloyd’s Railroad Map of the Southeastern States shows that

Brunswick had a railroad line by at least 1862.

Because of it’s proximity to the Federal blockading fleet and the

Union troops that occupied nearby St. Simons Island, Brunswick’s

inhabitants fled to the interior during the early stages of the

Civil War. When the citizens returned in 1865, they found the

town dilapidated, but otherwise intact. Aided by northern

entrepreneurs, Brunswick’s citizens immediately began a period of

rebuilding. The economic success that followed was based

largely on the lumber and naval stores industries. The

northern entrepreneurs that had moved to Brunswick in the decade

following the Civil War provided the money and jobs that were needed

for the town’s economic revitalization. For example, my

great-grandfather, John R. Cook, moved south from

Massachusetts with his younger brother in 1866 and chartered a

lumber business on the Brunswick waterfront. John and

George Cook chose Brunswick as a place to establish

their lumber business for several apparent reasons. First,

Brunswick was conveniently close to the vast stands of virgin yellow

pine that sprawled across millions of acres of the coastal plain.

Secondly, unlike Darien, its sister city to the north, Brunswick had

suffered few reprisals from Union troops during the war.

Consequently, the animosity felt by many southerners toward the

North at the close of the war was not strong in Brunswick.

With many of its homes and businesses intact, Brunswick was

physically prepared to resume normal activity in 1866.

Brunswick’s citizens were eager for employment and they welcomed

northern entrepreneurs with open arms. By 1870, so many

northern businessmen lived on Union Street that the native residents

called the area “Yankee Ville.” In 1885 the population of

Brunswick was 5,000. However, four years later the population

had skyrocketed to 9,800. Local newspapers documented the

town’s growth with a variety of articles and short business clips.

Foremost in the business increase, were immense shipments of sawn

pg. 2 |

|

pg. 3

timber. For example, during the months of

May and June 1877 over 2,000,000 board feet of lumber were shipped

from Cook Brothers & Company alone. The good economy with its

positive cash flow created a new consumer market, which resulted in

a variety of small retail businesses sprouting up all over town.

The people that worked in Brunswick could afford luxuries unheard of

in previous years. Included in the list of newly affordable

goods were cold beverages that quenched a worker’s thirst during and

after a hard day’s work in the hot southern sun. In the early

1880’s local newspapers carried advertisements for “ice cold soda

water” sold “by the glass” at local drug stores. However, the

consumption habits of people were changing. Soda water and

beer, which had previously been drawn into a glass or mug, were

being taken home in bottles. Savannah bottlers, such as

James Ray, Henry Kuck, Henry Lubs,

and John Ryan actively competed for the Brunswick

market in the 1870s and 1880s (see page 64). Unfortunately for

them, their beverages came in return bottles which bore the cost of

two way shipment. By the middle 1880s the expense of supplying

a town 70 miles away was too much for the Savannah bottlers to bear.

Their withdrawal from the beverage market created an incentive for

local bottling companies to appear.

pg. 3 |

|

pg. 4

CHAPTER TWO—THE

HISTORY AND TECHNOLOGY OF SODA WATER AND BEER

PART ONE—SODA

WATER

In the early nineteenth century soda water was only one of many

different varieties of naturally occurring spring water known as

“mineral water.” Coming from freely flowing springs, mineral

waters contained small amounts of various mineral compounds, such as

Magnesium, lithium, and potassium chlorides, hydrogen sulfide

(sulfur), and carbon dioxide that gave them a distinctive taste.

It was commonly believed that most types of mineral water had the

ability to impart good health when consumed or bathed in.

Springs in different locations had different chemical compositions

and presumably, different health benefits. By the 1820’s many

of the major springs, particularly those

In the early nineteenth century soda water was only one of many

different varieties of naturally occurring spring water known as

“mineral water.” Coming from freely flowing springs, mineral

waters contained small amounts of various mineral compounds, such as

Magnesium, lithium, and potassium chlorides, hydrogen sulfide

(sulfur), and carbon dioxide that gave them a distinctive taste.

It was commonly believed that most types of mineral water had the

ability to impart good health when consumed or bathed in.

Springs in different locations had different chemical compositions

and presumably, different health benefits. By the 1820’s many

of the major springs, particularly those around Saratoga, New York, had been commercialized with the

construction of bathing facilities and hotels. With an eager

eye for business, owners began bottling their spring water and

shipping it to distant locations. Probably, the most popular

water was that bottled at the Congress Spring in New York.

Congress Spring water bottles are found throughout the eastern

United States. Beyond its purported healthy qualities, spring

water containing carbon dioxide was especially tasty when small

amounts of fruit juice or other flavorings were added to it.

So great was the demand for this modified “mineral water” that

southern entrepreneurs began to manufacture it from ordinary well

water. This was accomplished by dissolving artificially

produced carbon dioxide gas in cool water. The concentration

of carbon dioxide in the artificial “mineral water” could be much

greater than in the natural variety. In the artificial mineral

water, the gas would fizz quickly out of solution unless it was

sealed under pressure in a bottle. The fact that traditional

glass bottles would burst from the increased pressure, led to the

development of smaller glass bottles with thicker walls. In

the two decades before the civil war, “mineral waters,” particularly

the “carbonic” (carbon dioxide) type, became increasingly popular

and all major cities in the eastern United States had “mineral

water” bottlers. These bottlers often advertised their product

with colorful bottles embossed with their name.

around Saratoga, New York, had been commercialized with the

construction of bathing facilities and hotels. With an eager

eye for business, owners began bottling their spring water and

shipping it to distant locations. Probably, the most popular

water was that bottled at the Congress Spring in New York.

Congress Spring water bottles are found throughout the eastern

United States. Beyond its purported healthy qualities, spring

water containing carbon dioxide was especially tasty when small

amounts of fruit juice or other flavorings were added to it.

So great was the demand for this modified “mineral water” that

southern entrepreneurs began to manufacture it from ordinary well

water. This was accomplished by dissolving artificially

produced carbon dioxide gas in cool water. The concentration

of carbon dioxide in the artificial “mineral water” could be much

greater than in the natural variety. In the artificial mineral

water, the gas would fizz quickly out of solution unless it was

sealed under pressure in a bottle. The fact that traditional

glass bottles would burst from the increased pressure, led to the

development of smaller glass bottles with thicker walls. In

the two decades before the civil war, “mineral waters,” particularly

the “carbonic” (carbon dioxide) type, became increasingly popular

and all major cities in the eastern United States had “mineral

water” bottlers. These bottlers often advertised their product

with colorful bottles embossed with their name.

pg. 4 |

|

pg. 5

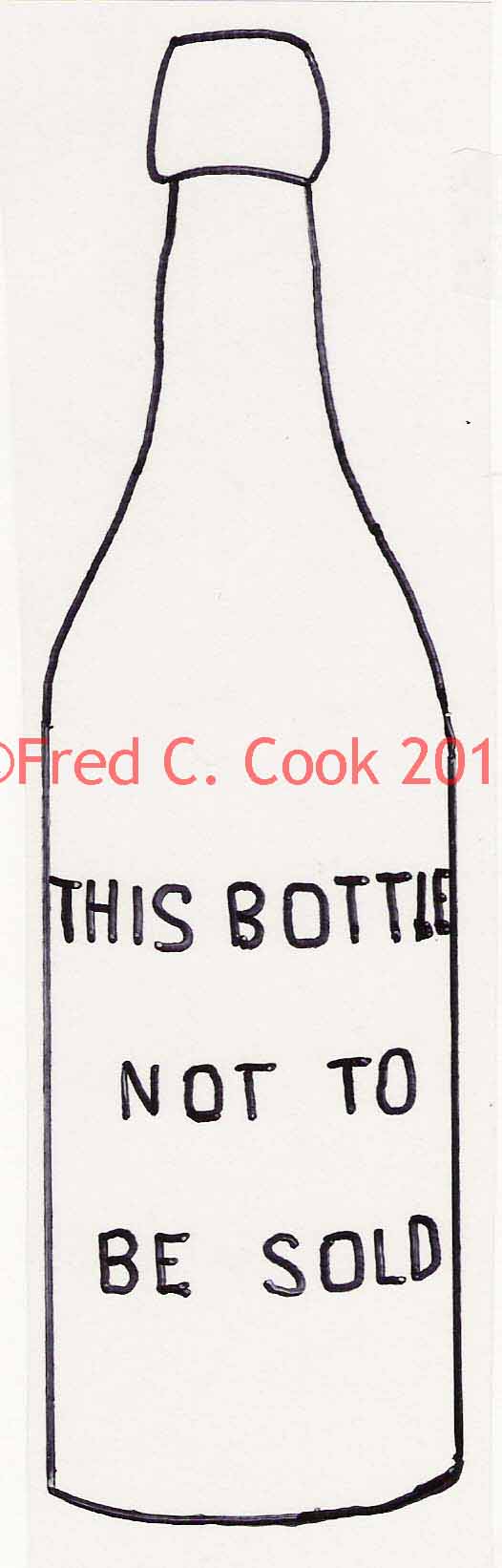

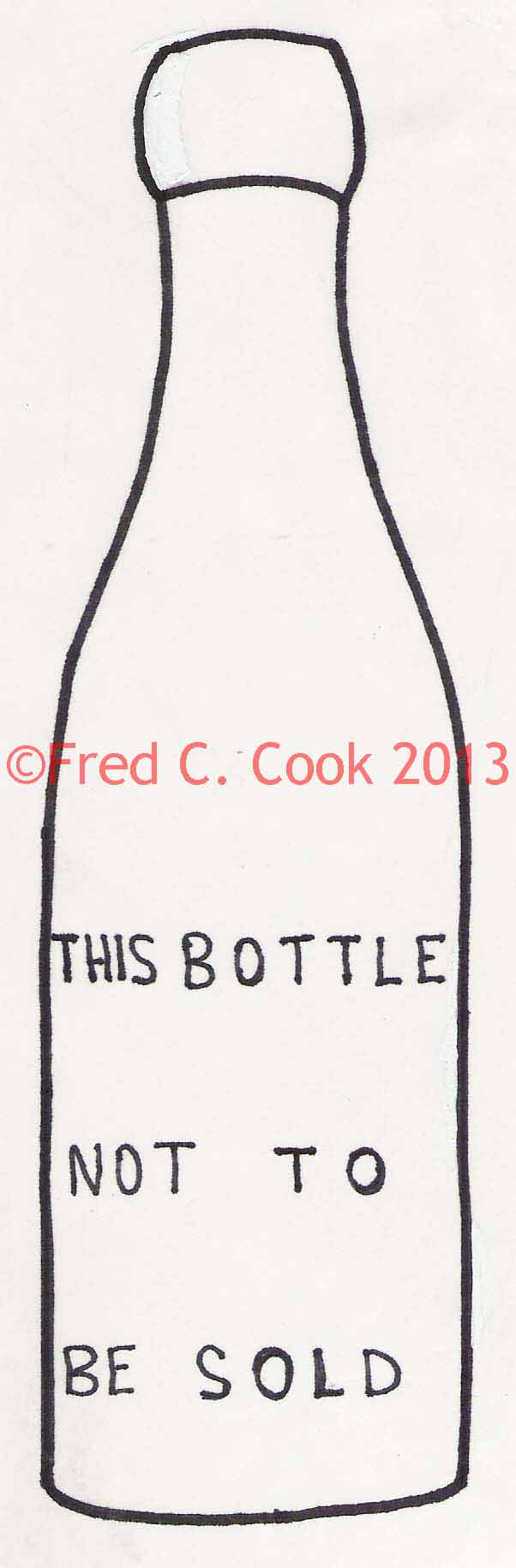

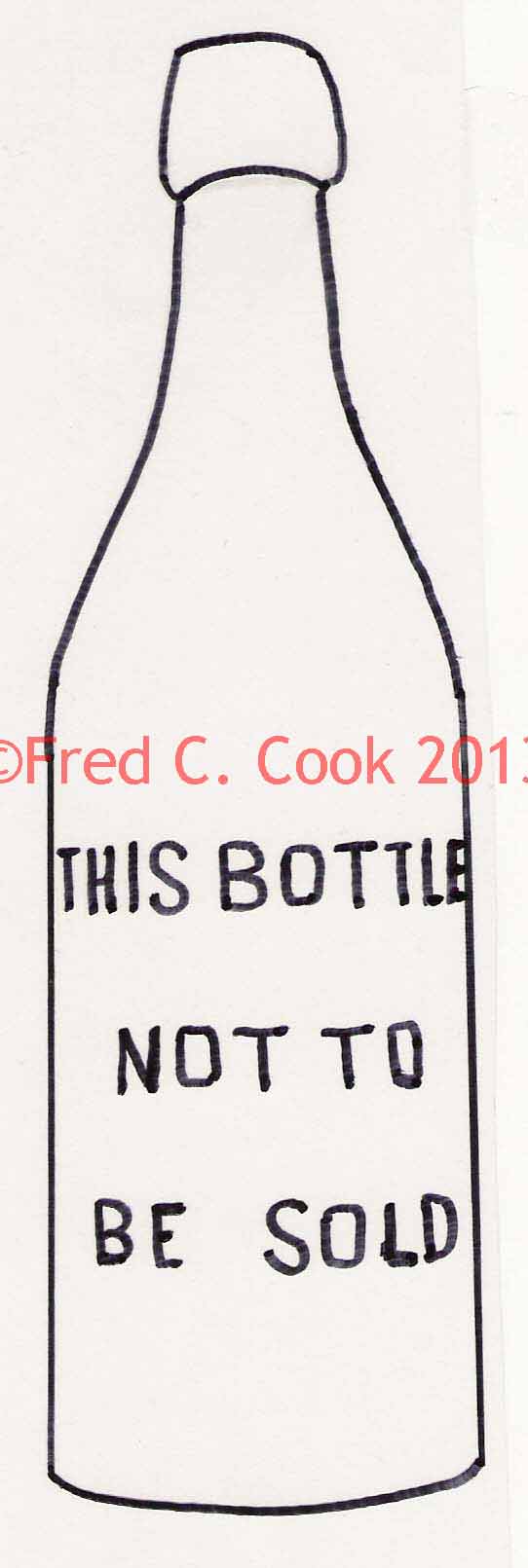

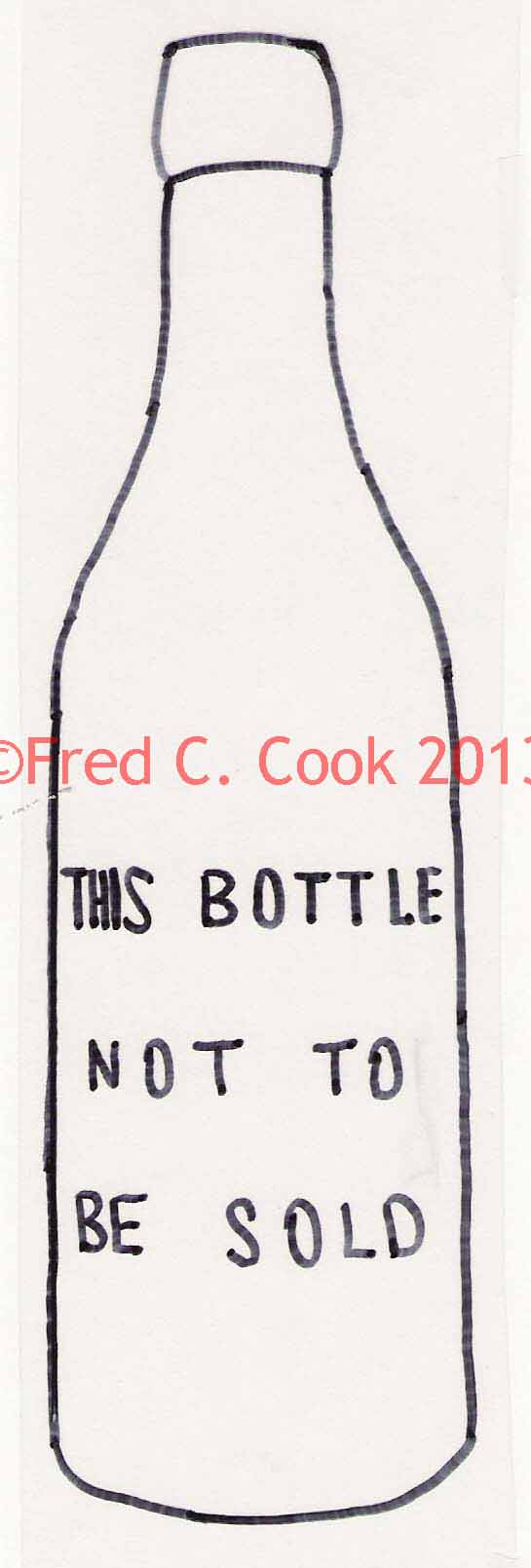

Shown on the preceding page is a cobalt blue

“JOHN RYAN EXCELSIOR MINERAL WATER” bottle from nearby Savannah,

Georgia, that dates to about 1855. The same embossing and a

reminder that “THIS BOTTLE IS NEVER SOLD” provided some degree of

assurance that these relatively expensive bottles would find their

way back to the bottler for refilling.

By the 1850’s, the specific term “soda water” began to replace the

more general term, “mineral water.” The new name was derived

from the chemical process by which carbon dioxide was commonly

manufactured. Today, every school child knows that you can

make a model volcano erupt, that is fizz, by pouring vinegar (a weak

liquid acid) onto baking soda (sodium bicarbonate, a solid source of

carbon dioxide gas) in its central crater. Thus, the term

“soda” in “soda water” is a derivative of the principal element’s

name, “sodium.” So, one way of making soda water is to create

carbon dioxide gas from baking soda and an acid and then force the

gas to flow into cool water where it will dissolve; thus forming

carbonated water. Even on a commercial scale, the production

of carbon dioxide is quite simple. Allow an acid substance to

react with a solid compound containing carbon dioxide (these

compounds are called carbonates). However, a technological

problem arises when certain chemicals are used. For example,

when a cheap strong acid, such as sulfuric acid, is poured onto

sodium bicarbonate or sodium carbonate, the carbon dioxide gas is

evolved in a rapid and uncontrolled way. In a sealed

container, the gas does not have time to dissolve in the water to be

carbonated and a dangerously high pressure results. Early soda

machine inventors were well aware of the fact that excessive

pressure could burst the carbonating vessel.

Patents registered with the United States Patent Office are good

sources of information about devices that were used in the

nineteenth century to produce artificial soda water. They

provide us with a time line of technology that was available to

bottlers. However, in using this information to interpret

nineteenth century technology, one must understand that the time

between the filing of a patent and the actual availability of the

device patented could have ranged from a few months to a number of

years. Also, machines that were cheap and effective could have

remained on the market and/or in use for years or even decades.

The first soda machines were relatively simple, but inherent in most

designs was a way to deal with the problem of rapid gas evolution.

One soda machine, invented by E.D. Wheeler of Murfreesboro,

Tennessee, patented in 1858, considered this problem paramount in

its design (See

illustration below). Wheeler stated

that, “The object of my invention is so to charge the generator with

the substances producing the carbonic acid gas, that the gas shall

be slowly and progressively evolved…” Wheeler further

testified that, “This mode of charging prevents the rapid generation

of gas which takes place under the ordinary method, and thus

relieves the apparatus from the undue pressure of such rapid

generation.” His device, shown below, presumably accomplished

the advertised safe generation of gas by enclosing the charge,

sodium carbonate and tartaric acid (a solid acid that requires water

to react), in a cloth bag (A). The reaction between these two

substances was controlled by the slow absorption of water by the

cloth bag. The carbon dioxide produced by the reaction passed

upward and then down through a pipe (P') into the main body of the

apparatus. The lower part of the pipe had perforations that

were designed to distribute the gas evenly into the water to be

carbonated (F). Wheeler’s patent included directions on

how to modify the generator to use more volatile,

pg. 5 |

|

pg. 6

but less expensive, marble dust (calcium

carbonate) and sulfuric acid (battery acid) as reactants.

Another small, but more complicated, generator was patented by

Hermann Pietsch of Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1874 (see

illustration below). His device controlled the production of

carbon dioxide by allowing gas pressure to stretch the rubber top of

the generator and simultaneously push the main body of the vessel

(D) downward against a spring. This movement lowered the acid

away from the marble chips (C) upon which it reacted. The

carbon dioxide gas could be drawn off periodically at valve P and

piped to another vessel containing the water to be carbonated.

As the gas was drawn off at valve P, the pressure in the generator

decreased and allowed the spring the move the acid upward where it

would again react with the marble chips. The pressure in the

reactor could be controlled at a safe level by adjusting the

spring’s tension. Vessel W was a scrubber or washer that

removed unwanted acid mist from the gas.

Click on images to see larger picture

Both of the machines shown above were small units, simple to operate

and relatively inexpensive; therefore, ideal for a grocer or

independent small scale bottler, who did not want to make a large

capital investment. Wheeler advertised his machine as being

suitable for “home use.” The cost necessary to establish a

small home based soda

pg. 6 |

|

pg. 7

water business was incredibly low. In 1891,

T.B. Ferguson purchased a soda machine, one lot of bottles,

including seltzer siphons and a wagon, horse and harness for only

720 dollars (see page 22).

Patented in 1891, J.F. Wittemann’s design, shown below, was

larger, complicated and more suitable for use by large scale

bottling plants. Due to its complexity, its method of

operation will not be discussed here.

It is interesting to note, that by the late 1880’s most of the new

carbonator patent designs employed the use of a cylinder of

compressed carbon dioxide gas. People were not submitting as

many designs for machines that made their own carbon dioxide gas

with sulfuric acid and other dangerous chemicals. Shown below

is a carbonator design patented by P.E. Malmstrom in 1892.

His device used a cylinder of compressed carbon dioxide gas to

produce soda water. This machine was relatively uncomplicated

and it produced a soda water solution by simply moving a handle back

and forth. In using this machine, the compressed carbon

dioxide cylinder valve (B) was opened, allowing the gas to flow to a

double valve (H/I). The double valve could be positioned so as

to allow the gas to enter vessel R or S, both of which contained

water. As the gas began to dissolve in the water, manipulation

of valve/s H/I made the solution flow back and forth from vessel to

vessel through tube T. The direction of the flow was

determined by the position of the valve/s. Malstrom

claimed that by “alternating the valves H, I a sufficient number of

times the water is thoroughly agitated and impregnated by the

carbonic acid".

Click images to see larger picture

pg. 7 |

|

pg. 8

The wide variety of soda machine patents issued in the late

nineteenth century leaves us to wonder which designs were popular

with small town bottlers. Several factors contributed to their

choice. One is the availability and cost of compressed carbon

dioxide gas. In order for this gas to be efficiently

transported, it had to be compressed to such a degree that it became

a liquid. In this form it must be kept in a steel cylinder at

a pressure of several thousand pounds per square inch. The

machinery necessary to produce large quantities of gas and to

compress it to such a high pressure was found only in large

industrial cities, particularly those in the north. The cost

of the gas was high and the heavy cylinders were expensive to rent

and ship. These costs kept such modern technology out of the

hands of many small scale bottlers for years. Small soda-acid

machines were much more economical than machines that required

compressed gas. Another factor that favored the continued use

of soda-acid machines was their availability. When a bottler

changed his business interests, he would sell his equipment and/or

bottles to another individual at a bargain price (see pages

27 and

30).

PART TWO—BEER

For many centuries beer has been brewed using the same basic

ingredients and procedures. The equipment used in brewing is

similar, irregardless of whether the scale is large or small.

In this discussion of the brewing process, reference will be made to

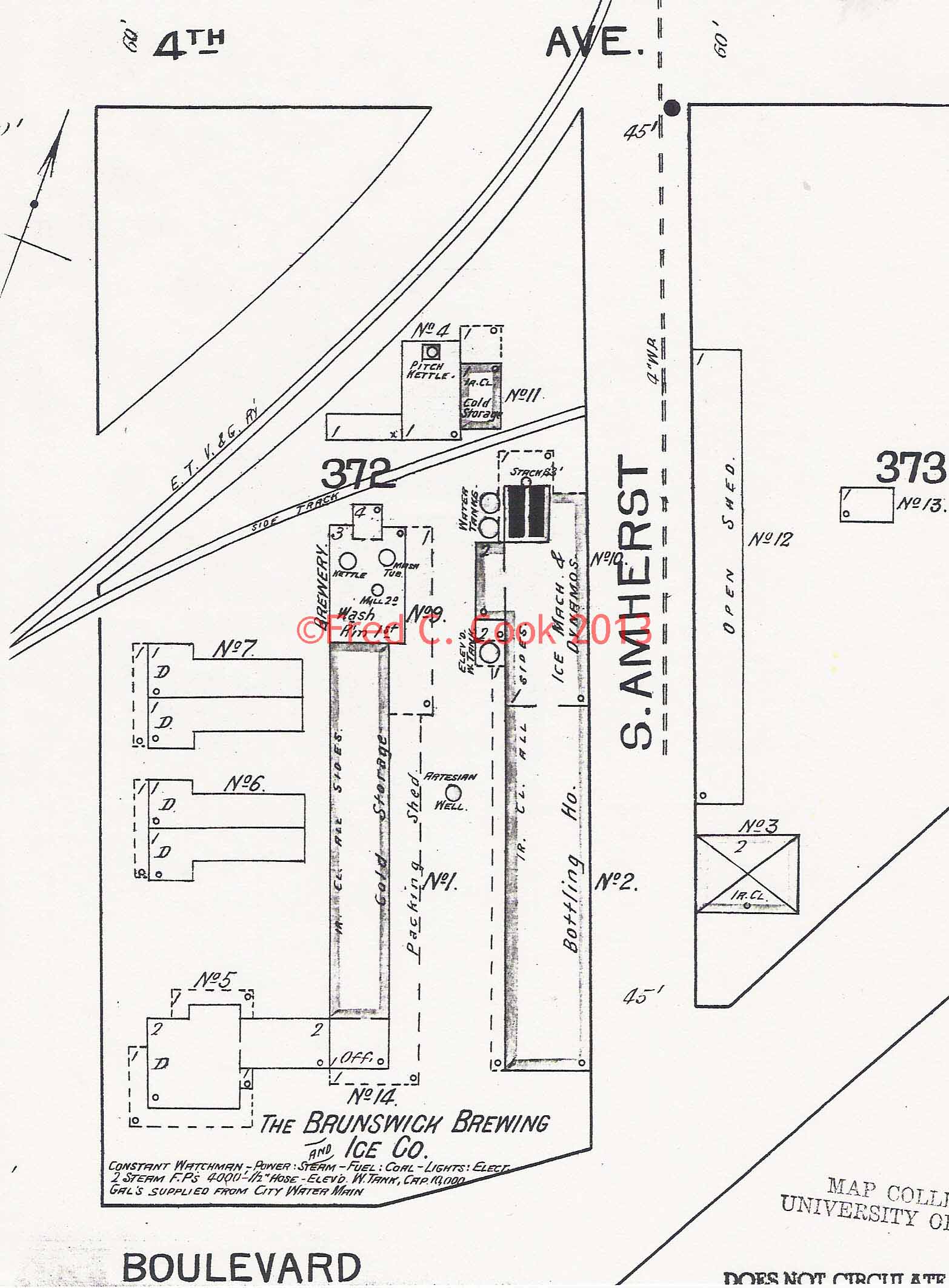

the map of Brunswick Brewing & Ice Company shown on

page 56 and the

equipment that it contained as listed on

pages 58-61.

The key ingredient in the brewing process is barley grain which has

been “malted” by allowing it to soak briefly in water. During

this process the barley grains begin to sprout or “germinate”.

When the sprout reaches a certain length, the germinating process is

stopped by drying the grains in a heated chamber. Certain

enzymes formed during germination have the ability to convert

starches in the seed into sugars, such as maltose, that can be

fermented into alcohol. Being a somewhat small scale brewery,

Brunswick Brewing & Ice Company purchased “malt” as opposed to

un-malted grain (see advertisement on page 57). This allowed

them to simplify brewing by avoiding the malting process and its

associated equipment. Therefore, at this facility, the first

processing step was to grind the malted grain into smaller pieces,

called “grist,” and separate them from the seed husk. Malted

grain was delivered to the BREWERY (page 56 map reference) also

called the BREWING HOUSE (page 58 document reference) building via

the side track of the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railroad.

Two elevators and conveyors raised the malt to the fourth floor of

the BREWERY where it was stored (see Map on page 56 and line 31 on

page 58). The “mill” shown on the second floor of the BREWERY

(see pages 55 and line 3 on

page 59) was the machine used to grind

the malted grain. The resulting grist was then weighed,

probably with the “large scale,” referred to in line 31 on page 58,

and then transferred to a large copper vat called a “mash tun” where

it was mixed with warm water. In this case the “mash tun” was

on the third floor of the BREWERY (page 55). In the mash tun,

water heated to 120-160 degrees Fahrenheit caused the enzymes to

reactivate. During this process, called “mashing,” the

reactivated enzymes break down most of the seed’s starch into

fermentable sugars. Additional starchy grains, such as corn

grist, called “adjuncts” may have been added during mashing.

The use of adjuncts in brewing was an American

pg. 8 |

|

pg. 9

innovation that provided an economical way to

increase the percentage of fermentable sugars in the filtered

liquid. However, the use of adjuncts is still literally

“against the law” in Germany. Brunswick Brewing & Ice’s

advertisement of German style beers leaves us to wonder if they used

adjuncts in their brewing process. After the mashing process

was completed, the enzyme activity was halted by heating the mixture

to 175 degrees Fahrenheit. The sugary liquid was then strained

from the remaining solid mass in a process called “lautering".

The mash tun was equipped with some sort of “false bottom” that

contained perforations that acted like a strainer. The grain

husks formed a natural filter bed that assists in the straining

process and a clear liquid called “wort” (pronounced wurt) flowed

from the bottom of the vessel. The “low bottoms” referred to

in line ten on

page 60 were probably false bottoms. In a

process called “sparging,” hot water is sprinkled over the spent

solids in the mash tun. This process recovers the last traces

of sugary liquid from the wort. The copper sprinklers referred

to on line eleven of

page 60 were probably used for sparging.

After lautering, the wort was moved to another vessel called the”

brew kettle” where it was heated to boiling. At Brunswick

Brewing & Ice Company, this vessel was also located on the third

floor of the BREWERY. Carefully weighed hops were added during

the boiling process. The scales referred to in line three on

page 60 was likely used for weighing hops. The resins

extracted from the hops helped to preserve the finished beer and add

bitterness that off set the sweetness of any remaining unfermented

sugars. The brew kettle at this facility was probably heated

with steam produced by two 100 horsepower boilers positioned at the

north end of the ICE MACHINE & DYNAMO room (page 56). For

lager type fermentation, the hot wort must be cooled to a

temperature of about 45 degrees Fahrenheit. This was

accomplished at the local brewery with a large copper cooler

supplied with refrigerated water from the ice plant (page 56).

In the traditional process, the wort flows to a “pitch kettle” (page

56 building No. 4 and line thirty-two on

page 59) where it is

thoroughly aerated before yeast is “pitched” (added with stirring).

At this stage of fermentation the yeast requires oxygen for proper

growth. The “air pump” (line thirteen on

page 59) and

“pitching machine” (line thirty-two on

page 59) were used to aerate

and mix the wort with yeast. At Brunswick Brewing & Ice

Company, the pitch kettle was in a different building and it is

likely that the wort flowed by gravity, possibly through the 100

feet of large copper pipe referred to in line seven on

page 60.

Once yeast was added to the chilled wort, active fermentation began.

The beers produced at Brunswick Brewing & Ice Company were made with

a bottom fermenting yeast that produced lager style beer.

During the fermentation process, the main part of which requires two

or three weeks, the fermenting mixture must be kept in a cooled

vessel that excluded air. The introduction of oxygen from air

would cause spoilage of the finished beer. Fermentation

produced carbon dioxide gas which was recovered, stored and used

later to carbonate the beer. The fermentation at Brunswick

Brewing & Ice Company was carried out in one or more of the

1000-1200 barrel tubs mentioned in line twenty-six on

page 59.

The design of these tubs in not apparent, but they must have had

some sort of lid with piping to remove the carbon dioxide gas and

exclude air. After initial fermentation, the resulting “green

beer” is stored in a cold environment for a month or more until it

becomes adequately aged. Storage at the local brewery may have

been accomplished in the many various sized casks listed in line

twenty-six on

page 59. Either of the “Cold Storage” buildings

shown on

page 56 could have been used to house the casks of aging

beer. By the latter part of

pg. 9 |

|

pg. 10

the nineteenth century various filtering devices

were invented that “brightened” the finished beer by removing small

particles of sediment. One such device, invented by Otto

Zwietusch, was used at the Brunswick Brewing & Ice Company

facility (see illustration below and line seventeen on

page 59).

Although this device was patented in 1895, it is perfectly

conceivable that it was in use earlier. Even modern devices

are sometimes identified with “patent applied for”, a term that

indicates they were marketed before a patent was actually granted.

After “brightening,” the beer was sent to the

bottling house where it was pumped into wooden kegs or glass

bottles. The “100 brass spigots and 100 valves” mentioned in

line 21 of

page 59 probably accompanied the kegs to their retail

destination. Barreled and bottled beer was hauled by wagon to

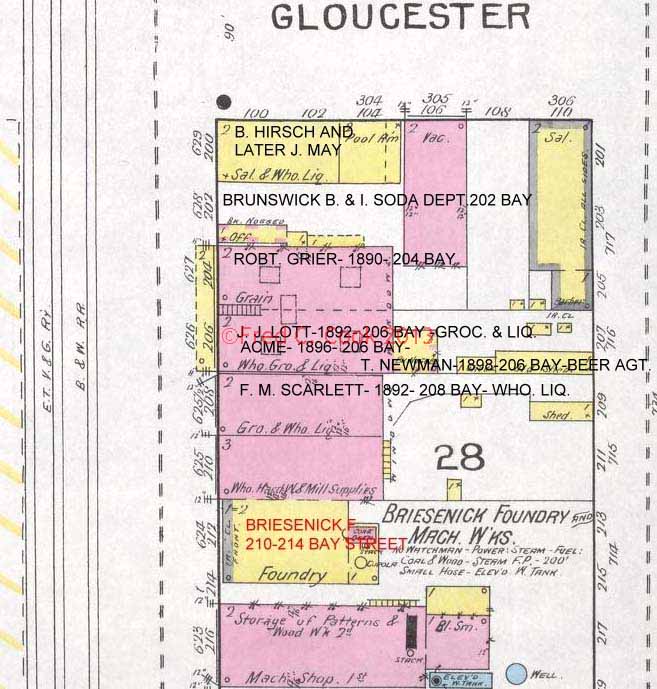

the Brunswick Brewing & Ice Company’s distribution center at 202 Bay

Street (See map on page 41).

PART THREE—BOTTLES

This section presents a description of the types of soda and beer

bottles that were used in Brunswick in the nineteenth century.

In general, these represent the most common types of contemporary

soda and beer bottles in use in the southeastern United States.

Click image to see larger picture

Blob top soda bottles—Blob top soda

bottles were in use as early as the 1830’s in Charleston, South

Carolina. These bottles were designed to withstand the

physical rigors of being repeatedly filled, emptied and returned to

the bottler (see page 4). Consequently,

pg. 10 |

|

pg. 11

they were made with a thick glass body to which

an even thicker glass “blob” top was fitted in a molten state (such

tops are said to be “applied”). By the late 1880's

improvements in glass technology allowed the entire bottle to be

molded in one operation. However, the sturdy blob top shape

was retained. Soda bottles usually had a capacity of 8-10

fluid ounces. Because blob top soda bottles and their

associated technology were still being used in the first decade of

the twentieth century, those bottlers and their bottles are included

in a special early twentieth century section.

Click image for larger picture |

Type 1—Blob

top soda bottles with Putnam closures—The

first blob top bottles were closed with a cork stopper that was held

in place by a thin copper wire. The wire was necessary to

secure the cork against pressure generated by the carbonic gas

(carbon dioxide) dissolved in the soda water. However,

twisting the wire into place was a cumbersome and time consuming

task. In 1859 Henry Putnam of Cleveland, Ohio

invented an improved design that became the most popular closure for

the next 25 years. Henry’s description of the closure

verifies its convenience and ease of operation: “Whenever it

is desirable to uncork a bottle, the thumbs are placed upon the

sides AA and the fastener shoved from off the top of the cork, which

is instantly forced out of the bottle by the expanding gas.”

Although there are no known examples of this type of bottle embossed

with “Brunswick, Georgia", at least one Brunswick bottler purchased,

for his own use, retired blob top bottles with Putnam

closures from northern and Midwestern companies (see page 24).

Type 2—Blob

top round bottomed bottles—Sometimes

called “torpedo” or “ballast” bottles, these glass containers

differed from the traditional cylindrical shape by having thick

round bottoms. These bottles appear in the early 1860’s as

part of the cargo shipped from the British Isles to American ports.

British round bottomed bottles have an

pg. 11 |

|

pg. 12

interesting history. For stability, British

sailing ships, bound for American ports, required a considerable

amount of weight in their lower hull to stabilize their tall sails.

Ballast stones, which were discarded when the ships reached port,

provided most of the needed mass. However, a cargo of thick

glass round bottom bottles containing ginger ale also served very

well as ballast. The bottles were not only useful for adding

weight, but they contained a product that could be easily marketed

in American ports. In fact, so common are these bottles in

southern harbor towns that local bottle collectors usually refer to

them as “ballast bottles". During shipment round bottomed

bottles were stacked on their side in order to keep their corks

damp, swollen and well sealed. The corks were secured by the

same type of thin copper wire that was used prior to 1860 by

American soda bottlers. In the 1870's round bottomed bottles

became so popular that they were manufactured in this country for

American bottlers. Several types of round bottomed bottles

bear the name of the Savannah bottler, John Ryan.

At least one Brunswick bottler, Taylor Ferguson,

acquired foreign made round bottomed bottles that came into the

Brunswick port. He refitted them with Putnam closures and

filled them with his own products (see pages

28-29).

Type

3—Blob

top soda bottles with Hutchinson closures—Henry

Hutchinson of Chicago attempted to make the traditional cork

soda bottle closure obsolete with the introduction of his new

design, which was patented in 1879. Henry’s stopper

design used gas pressure from the soda water in the bottle to seal

it by applying a force against a flexible rubber gasket positioned

in the bottle’s neck. The container was opened by pushing a

stiff wire attached to the stopper downward. The bottle could

be easily resealed by pulling the wire upward. Although easy

to operate this design was inherently unsanitary. Dust, dirt

and germs could easily collect in the neck of the bottle and become

mixed with the contents when the bottle was opened. In spite

of this design defect, the Hutchinson closure had almost

completely replaced the Putnam closure by the late 1880's,

when soda water was first bottled in Brunswick. This was not

the case in nearby Savannah, where the cork/Putnam closed

blob top bottle had reigned for almost half a century. In

spite of its size and demand for soda products, Savannah soda

businesses acquired and used very few Hutchinson bottles

during the 1890's. It appears that technological change came

slow to this large city. The principal reasoning is that by

the late 1880's the Savannah bottlers had a huge investment in cork/Putnam

closed blob top bottles and the machinery that filled them. It

was much easier for new bottlers, such as Type

3—Blob

top soda bottles with Hutchinson closures—Henry

Hutchinson of Chicago attempted to make the traditional cork

soda bottle closure obsolete with the introduction of his new

design, which was patented in 1879. Henry’s stopper

design used gas pressure from the soda water in the bottle to seal

it by applying a force against a flexible rubber gasket positioned

in the bottle’s neck. The container was opened by pushing a

stiff wire attached to the stopper downward. The bottle could

be easily resealed by pulling the wire upward. Although easy

to operate this design was inherently unsanitary. Dust, dirt

and germs could easily collect in the neck of the bottle and become

mixed with the contents when the bottle was opened. In spite

of this design defect, the Hutchinson closure had almost

completely replaced the Putnam closure by the late 1880's,

when soda water was first bottled in Brunswick. This was not

the case in nearby Savannah, where the cork/Putnam closed

blob top bottle had reigned for almost half a century. In

spite of its size and demand for soda products, Savannah soda

businesses acquired and used very few Hutchinson bottles

during the 1890's. It appears that technological change came

slow to this large city. The principal reasoning is that by

the late 1880's the Savannah bottlers had a huge investment in cork/Putnam

closed blob top bottles and the machinery that filled them. It

was much easier for new bottlers, such as

pg. 12 |

|

pg. 13

those in Brunswick, to invest in Hutchinson

bottle technology than it was for an older established bottler to

replace his entire inventory of bottles and filling equipment.

The concept of technological upgrade may explain how Brunswick

bottler, Taylor Ferguson, happened to acquire cork/Putnam

closed blob top bottles from northern bottling companies at cut rate

prices (see page 24).

As mentioned above, the change in technology from cork/Putnam

closures to Hutchinson closures in the late 1880's is

reflected by the fact that all blob top soda bottles embossed with

the name of a Brunswick bottler are of the Hutchinson type.

Type 4—Seltzer

or siphon type bottles—At

least four Brunswick bottlers filled and distributed high pressure

soda water in these thick glass containers. All of the examples of

Brunswick siphon bottles found thus far were broken. None of these

were embossed or etched with a local bottler’s name. A somewhat

contemporary siphon bottle closure and its associated tool, patented

by John Brown of Medford, Massachusetts, are shown below. Because of

the high pressure of the carbonated water, these bottles seemed to

have required a complicated and expensive filling device, such as

the one invented by John Matthews. The siphon bottle shown below in

John Matthew’s filling machine is the same type of bottle that was

used by Taylor Ferguson of Brunswick.

|

|

|

|

Click images for larger

picture |

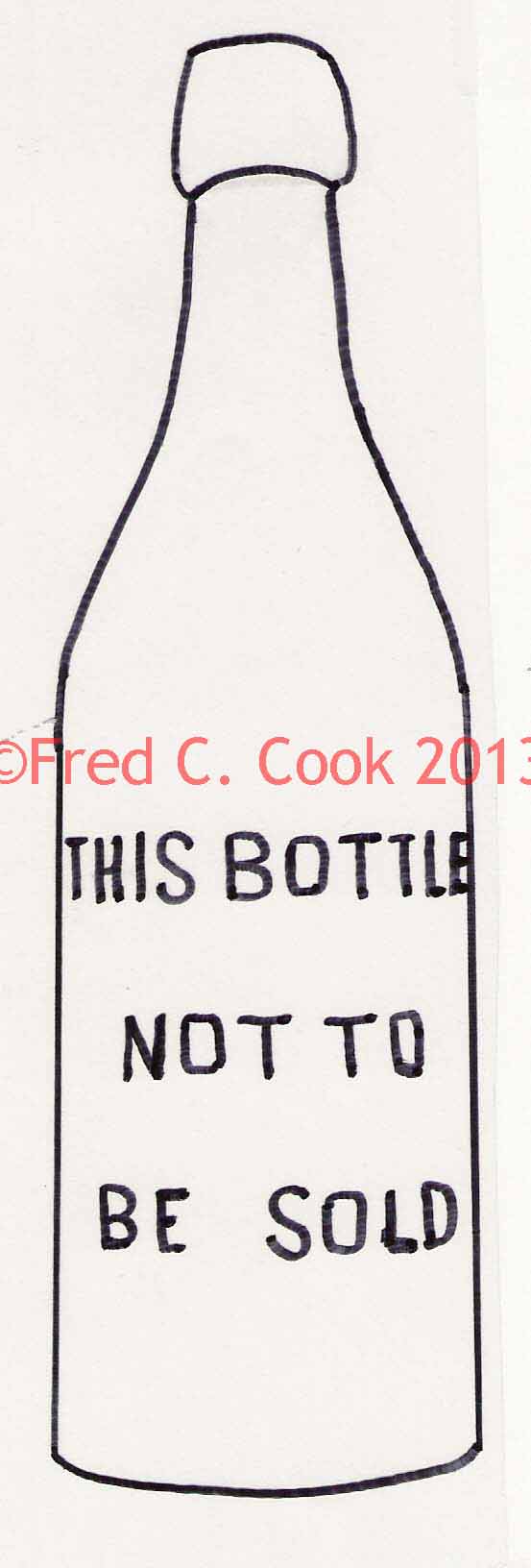

Beer bottles—The walls of these bottles

were generally thinner than soda bottles, probably because the beer

was not as highly carbonated as soda water and pressures within the

bottles was less. In general, beer bottles have a more

elongated cylindrical shape than soda bottles. Almost all of

the Brunswick beers have a capacity of 12-14 fluid ounces, but at

least one small bottle is known that has a capacity of only 7

½ ounces. The

pg. 13 |

|

pg. 14

no-return

beer bottles have a double collared top or blob top that was sealed

with a straight cork held in place by a simple twisted copper wire.

None of these bottles are embossed with a Brunswick bottler’s name.

All of the beer bottles, embossed “Brunswick”, have blob tops and

these were sealed with two different types of closures. no-return

beer bottles have a double collared top or blob top that was sealed

with a straight cork held in place by a simple twisted copper wire.

None of these bottles are embossed with a Brunswick bottler’s name.

All of the beer bottles, embossed “Brunswick”, have blob tops and

these were sealed with two different types of closures.

Type 1—Blob top beer bottles

with lightning closures—In 1876 Charles DeQuillfeldt

of New York City patented a new device that sealed a bottle by

forcing a rubber lined cap against the interior and exterior

surfaces of its lip by means of a lever like iron wire yoke.

Karl Hutter immediately purchased the rights for this

patent and began manufacturing the closure. Later, it became

known as the “lightning stopper". One Brunswick beer bottle, “Robert

Grier”, has “K. Hutter New York” embossed on its base.

The few bottles that have been found with the remains of their

closures indicate that the design present was more like that

patented by Johnson and Thatcher in 1886.

[Click images to see larger picture.]

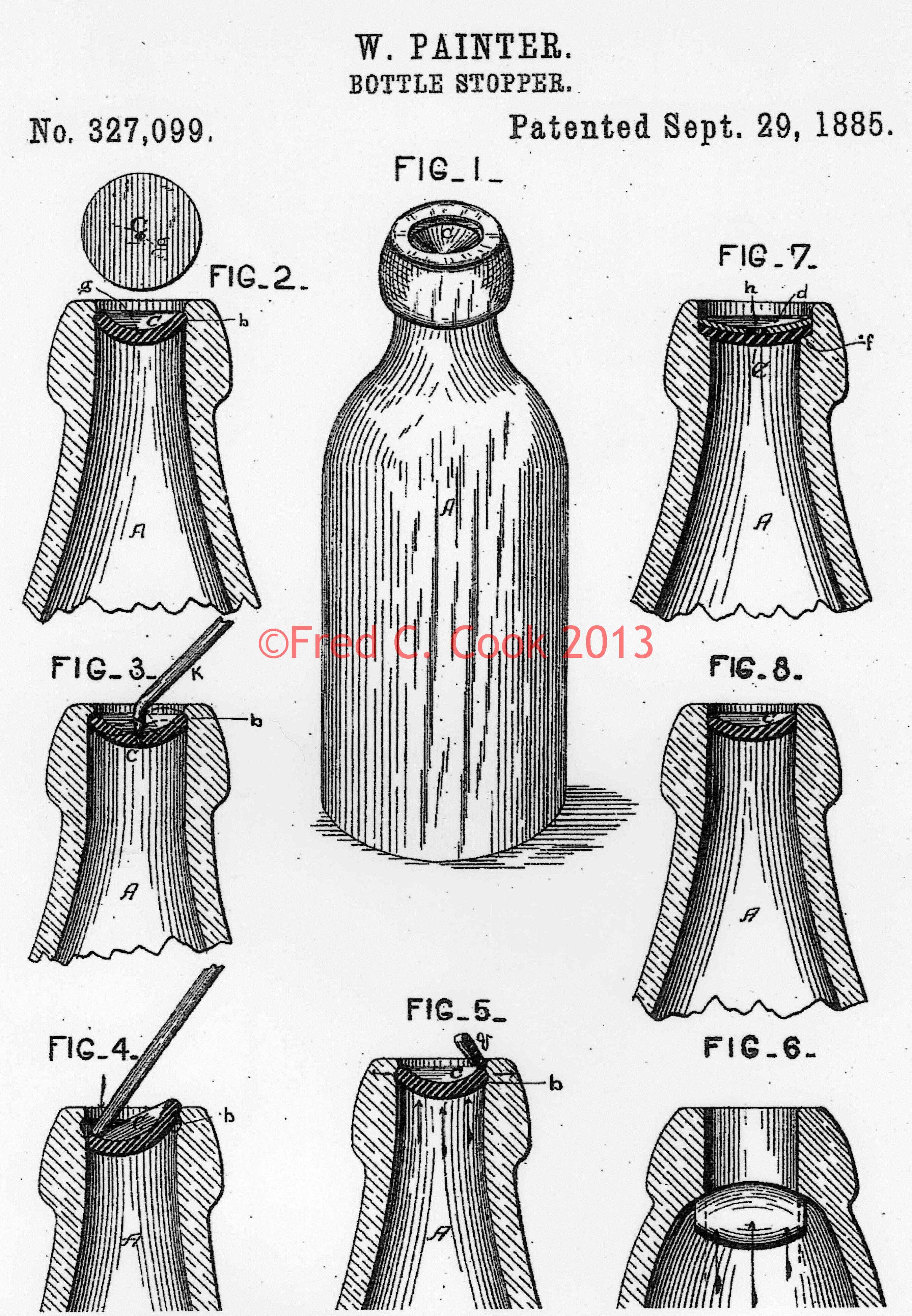

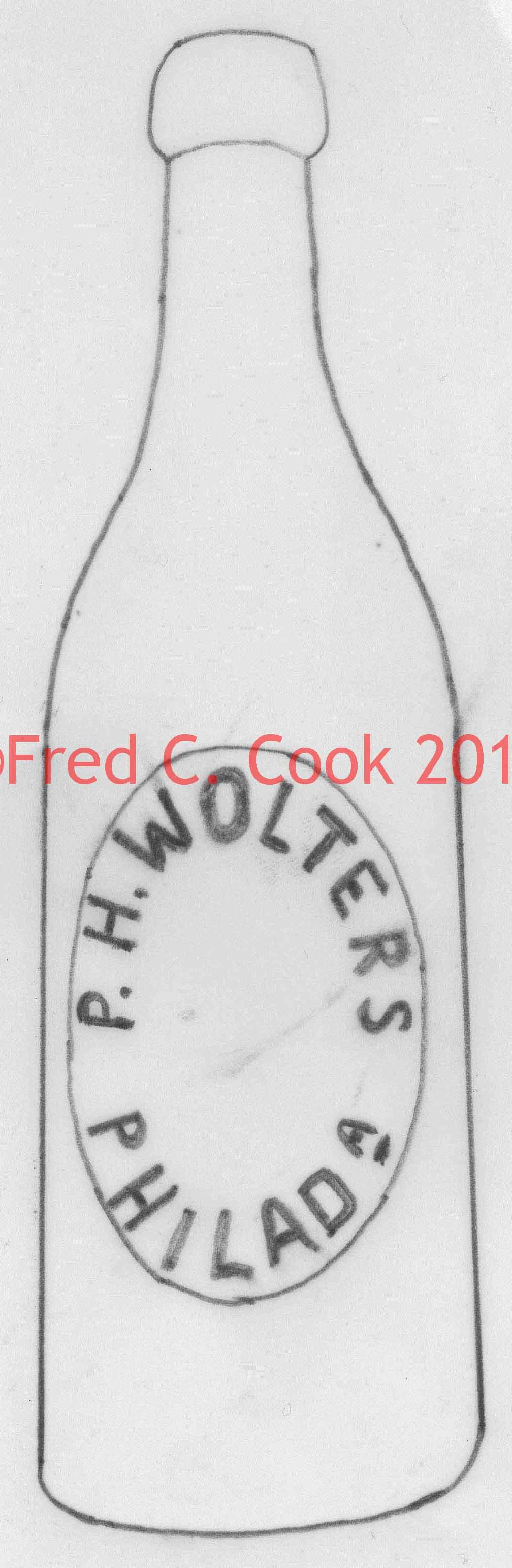

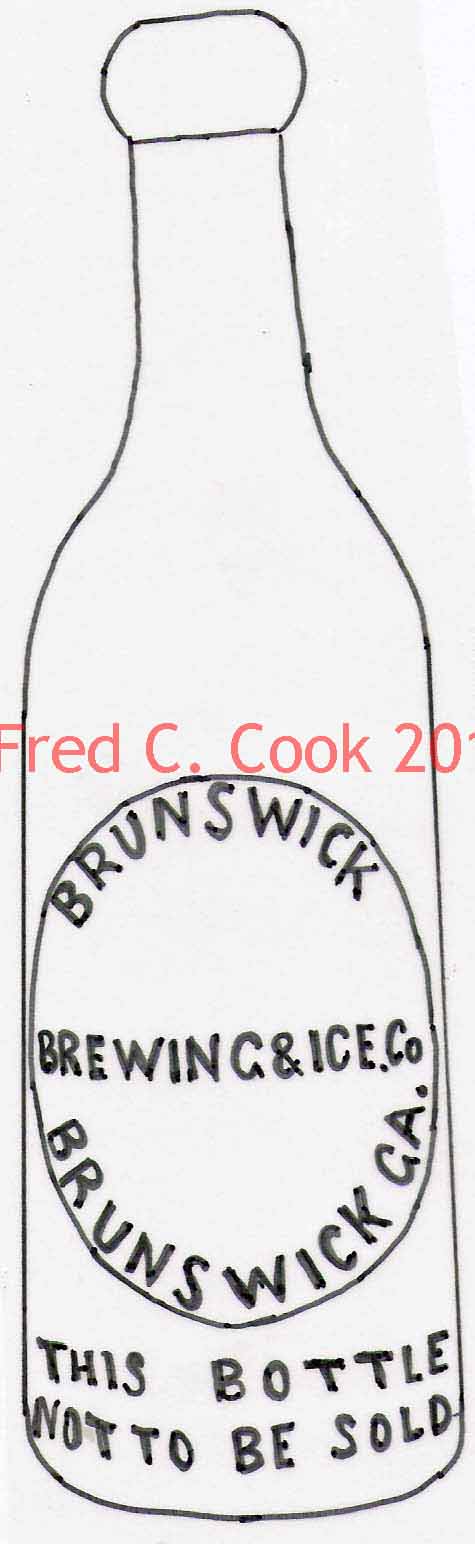

Type 2—Blob top beer bottles

with William Painter type closures—Beer bottles embossed with

“Brunswick Brewing & Ice Company” and P.H. Wolter

Philadelphia have closures that are of the type invented by

William Painter of Baltimore, Maryland in 1885.

This type is also referred to as the “Baltimore loop”. These

bottles had a groove in the interior of the applied blob top.

In filling with a carbonated beverage, such as beer, the bottle was

sealed by an inverted disk of flexible material, fixed into the

groove. The disc was smaller than the groove so it had an

internal bend that sealed the pressurized contents.

Frequently, it had a wire with a loop attached to its center.

To open the bottle a finger was inserted into the loop and adequate

pressure was applied to remove the disk.

pg. 14 |

|

pg. 15

William Painter’s Patent for the “Baltimore Loop.”

pg. 15 |

|

pg. 16

CHAPTER THREE—BRUNSWICK’S

NINETEENTH CENTURY SODA BOTTLERS

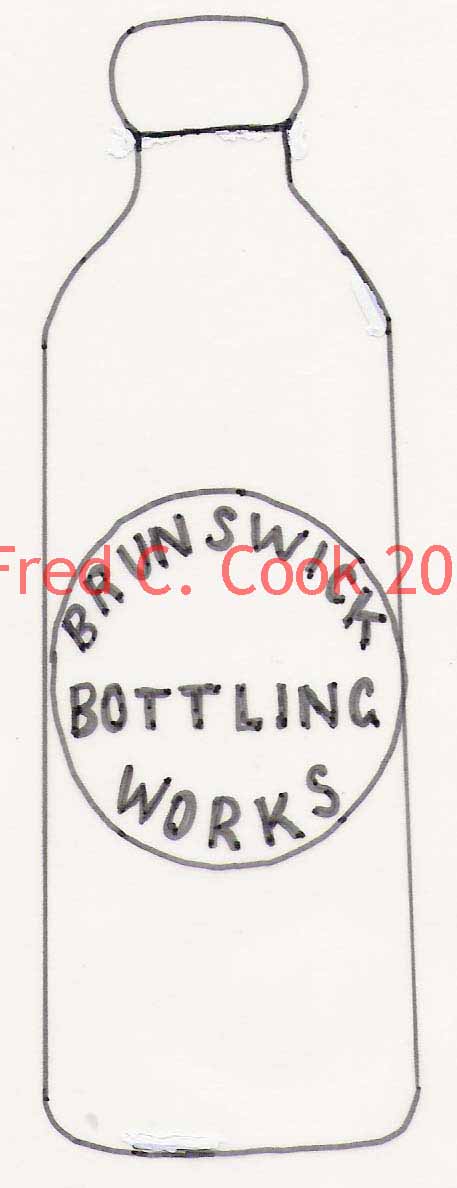

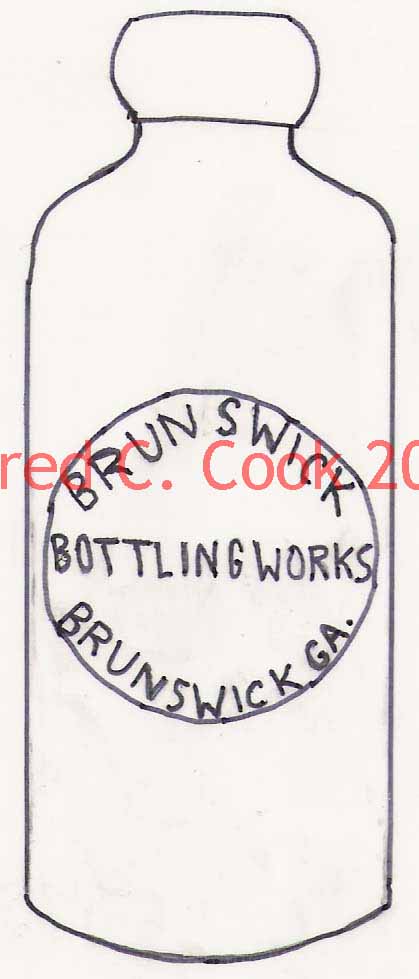

Brunswick Bottling Works—Little is known

of Brunswick Bottling Works. However, it was probably the

first company in Brunswick to bottle soda water. The company

was apparently out of business in 1890, when the first city

directory was published. The bottles owned by the proprietors

of Brunswick Bottling Works were sold to Brunswick Brewing & Ice

Company sometime after its establishment in 1889. Brunswick

Bottling Works was one of the two companies in Brunswick that used

bottles with applied tops. Most American glass works phased

this technology out in the late 1880’s; therefore, the pre-1890 date

assigned to this business is supported by the method by which these

bottles were produced and the company’s absence in the first city

directory. The only two types of Brunswick Bottling Works

bottles are shown below,

|

S101.1 -- Tall/aqua/applied top/soda/

Hutchinson stopper

Height -- 6 23/32”

Diameter -- 2 11/32” |

S101.2 -- Squat/aqua/applied top/ soda/

Hutchinson stopper

Height -- 6.0”

Diameter -- 2 7/16” |

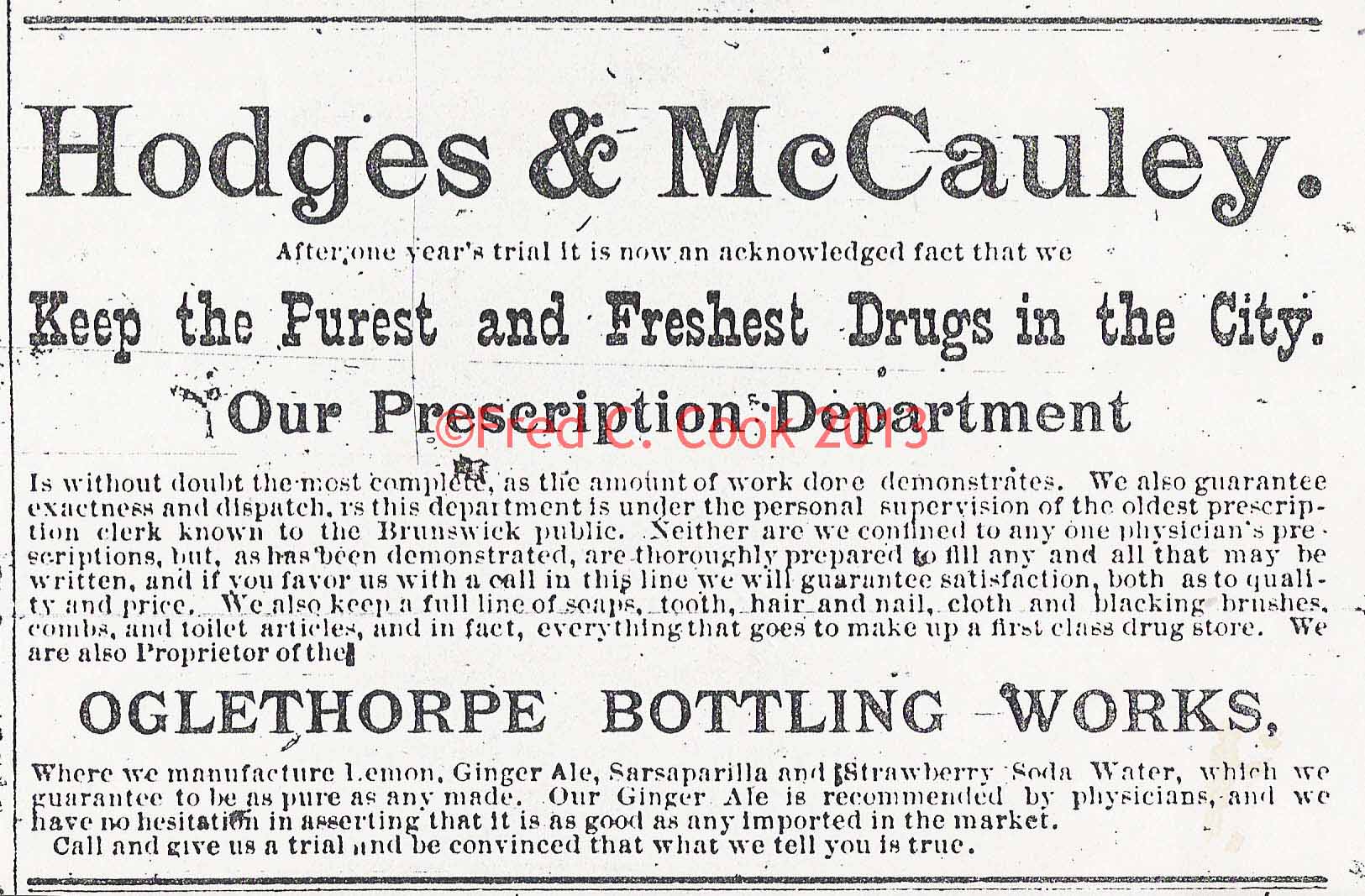

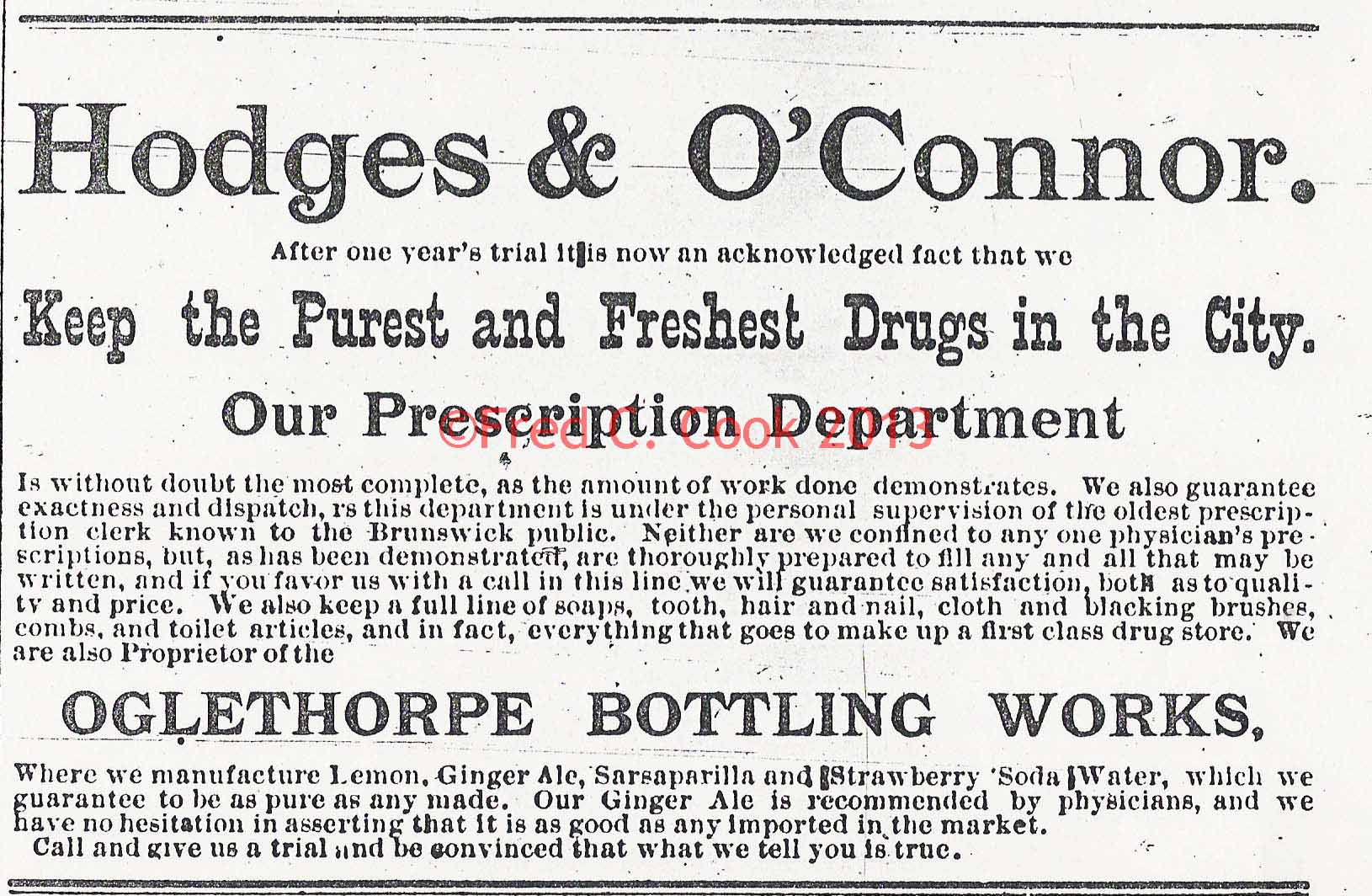

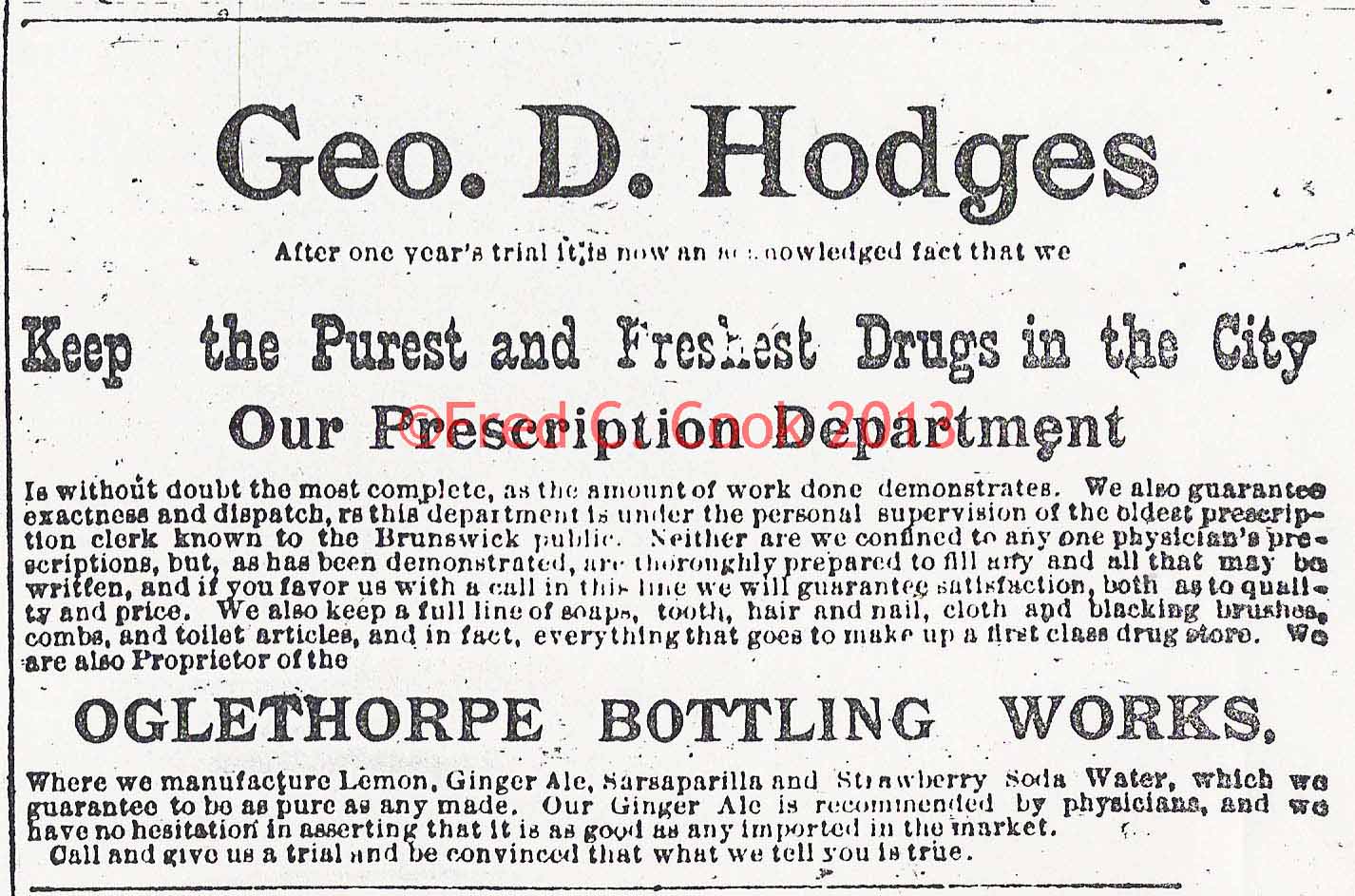

Oglethorpe Bottling Works—was owned and

operated briefly from 1887 to 1889 by George D. Hodges and

other investors. George Hodges was from Quitman,

Georgia, but it is not know when he moved to Brunswick.

However, George’s name appears in the registered voter lists

published in the Brunswick Daily Advertiser-Appeal at least as early

as December 5, 1885. As shown in the newspaper

advertisements on pages

19-20, Oglethorpe Bottling works probably

operated under the general proprietorship of George Hodges’

Drug Store. Several documents in the Glynn County Property

Records verify that George Hodges and George

McCauley were in business together as early as September 26,

1886 when they bought a safe for their business. On January

20, 1887 they bought a Fancy Siberian Arctic Dominion #1196 soda

fountain and two 14 gallon copper founts from James W.

Tufts in Boston, Massachusetts. The next year they made

two

pg. 16 |

|

pg. 17

related purchases. The first, purchased on

April 5, was equipment and siphon bottles, also from James

Tufts. The equipment included a Black & Fancy Siberian

Atlantic Constitution #772. The second, on November 18th

was a SGC(?) bottling table with a Number 2 solid plunge sink gauge

and Hutchinson attachment. The 1890 Brunswick City

Directory lists George Hodges as a druggist, but makes

no mention of Oglethorpe Bottling Works. As seen in the

newspaper advertisements below, Oglethorpe Bottling Works

manufactured a complete line of soda water, which included lemon,

ginger ale, sarsaparilla and strawberry flavors. The soda

bottles used by this firm all had applied tops, which, as mentioned

above, indicate that the business did not function after about 1890.

George Hodges’ name reappears in the 1892 city

directory as a mineral water bottler associated with C.O. Marlin

& Company located at 416 Bay Street. No bottles embossed with

C.O. Marlin are known to exist. George is not

advertised as a druggist in 1892 and it is not know if he was ever

legally qualified to practice pharmacy [According to Physician &

Druggist licenses in the Glynn County Probate Court, yes, George

was licensed,

click here--ALH] . His residence was a one story wood

frame house at 1003 Davis Street

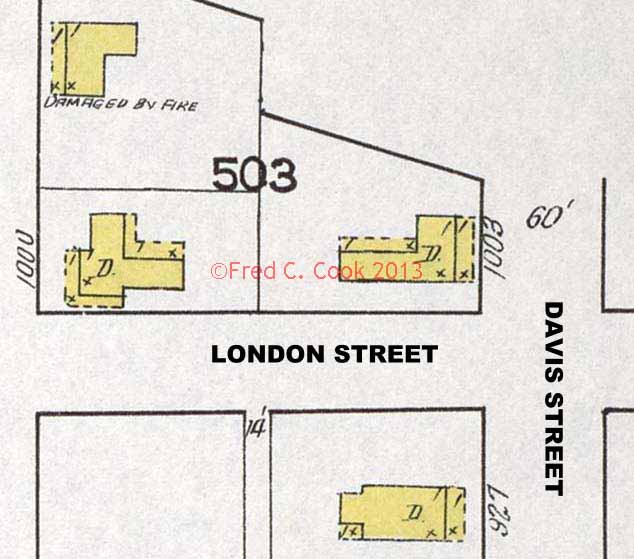

George Hodges house on the NW

corner of London & Davis Streets.

To the Right: “Geo.

D. Hodges Druggist Brunswick, GA.” pharmacy bottle. |

|

The following newspaper item shows that George

had a good sense of humor. This amusing story was told

directly to T.G. Stacey, editor of the Brunswick

Daily Advertiser-Appeal who published it on

Tuesday March 13, 1888:

A Big Man

Mr. George Hodges met us this morning and

told us that we might make the following announcement.

Said He: “I have

got the finest horse, the finest cow, the finest dog, the

finest boy and the prettiest wife in town, and to cap it all,

I am the ugliest man in town.”

pg. 17 |

|

pg. 18

Another personal mention in the same newspaper, published on the

previous Friday, follows:

Mr. George Hodges, is back from a trip to his old

home, Quitman. He reports everybody in that section

enthusiastic over the water-melon prospects. Every farmer in

reach of the railroad is putting in from 10 to 35 acres in melons.

The Southwest Ga. melon has gained a big reputation in the North and

Northwest, and always commands fair prices.

Brunswick Daily Advertiser-Appeal Wednesday January 18, 1888.

S102.1 Teal aqua/applied flat rim top/soda/Hutchinson stopper

Height- 6 13/16”

Diameter- 2 7/16”

|

S102.2 Teal aqua/ applied tapered rim top/soda/ Hutchinson

stopper.

Height- 7 .0”

Diameter- 2 7/16”

|

pg. 18 |

|

pg. 19

Brunswick Daily Advertiser-Appeal Monday

February 6, 1888.

Brunswick Daily Advertiser-Appeal Saturday

September 21, 1889.

pg. 19 |

|

pg. 20

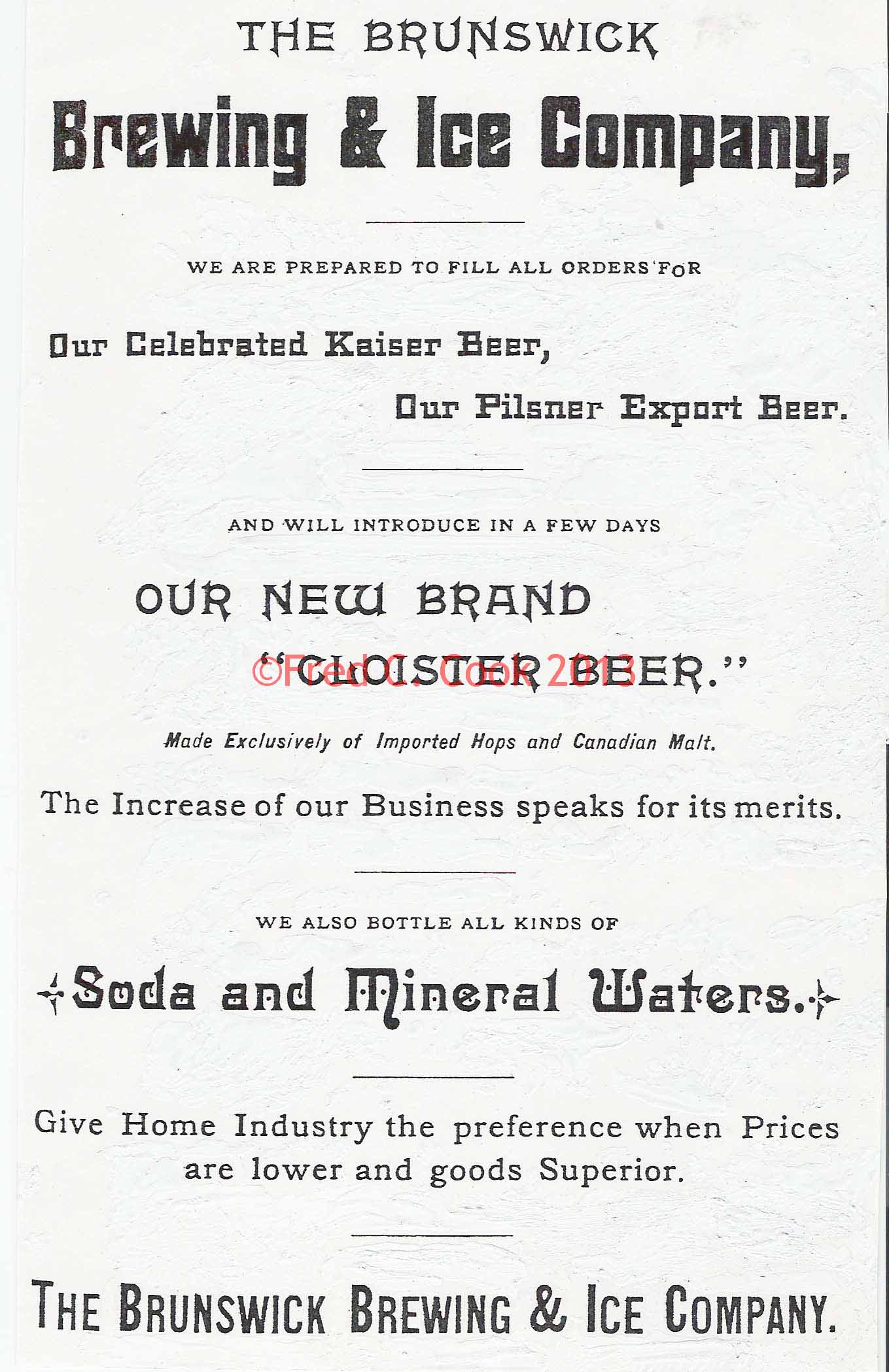

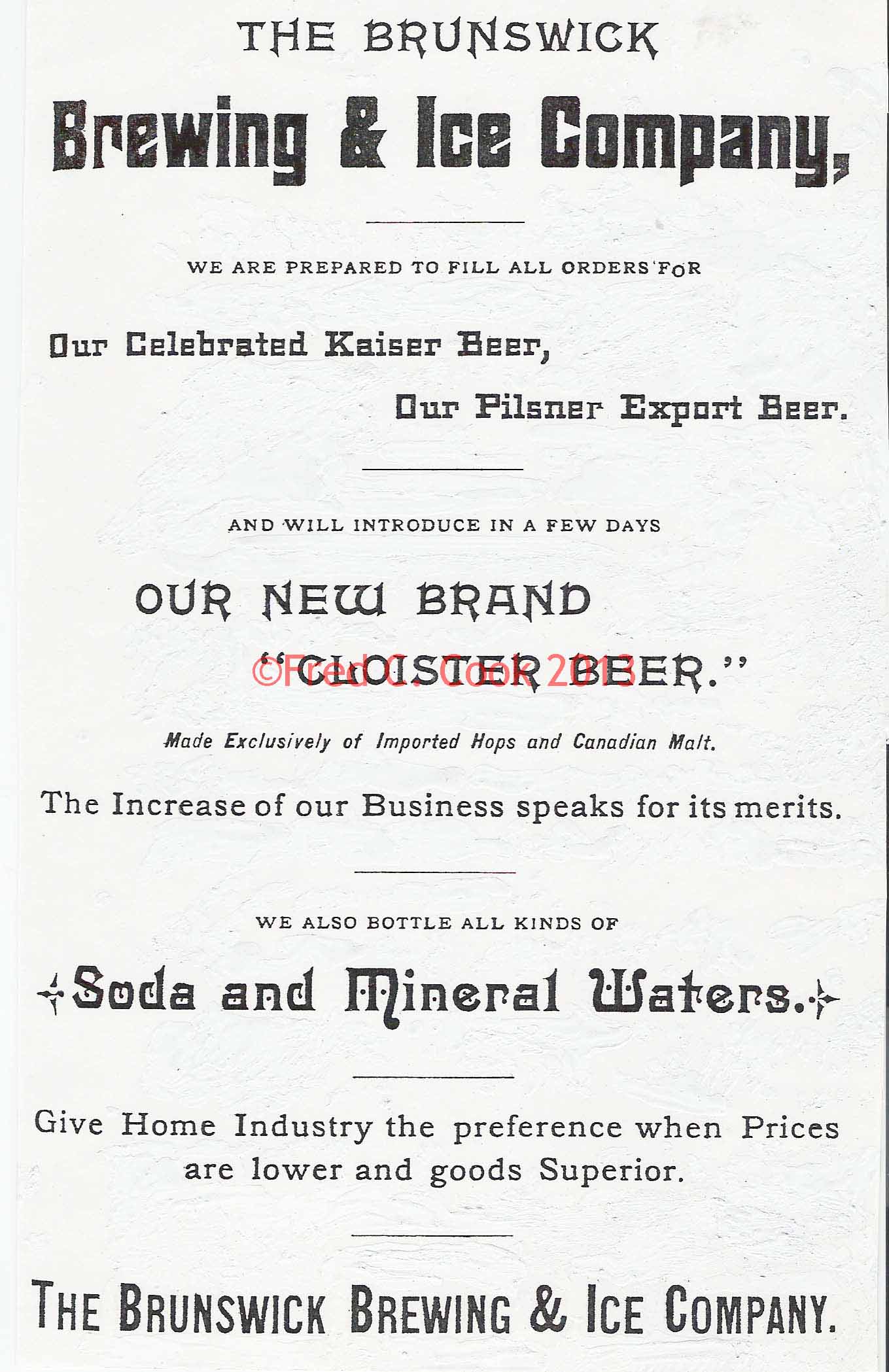

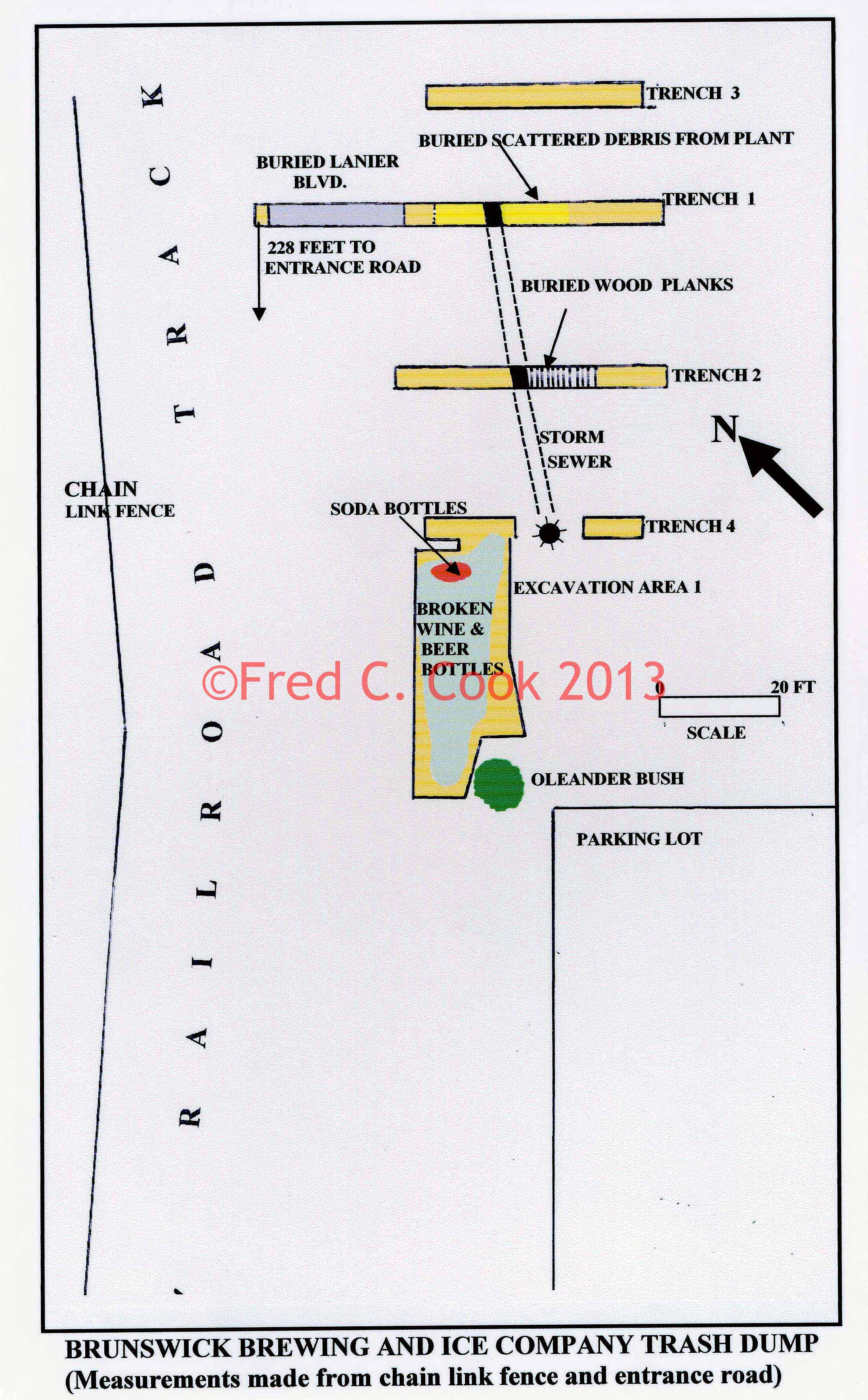

Brunswick Brewing & Ice Company—manufactured

beer, ice and soda water. The following advertisement appeared

in the 1892 city directory:

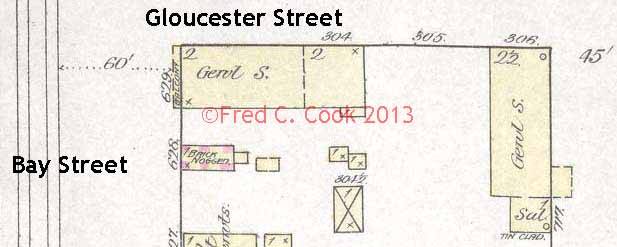

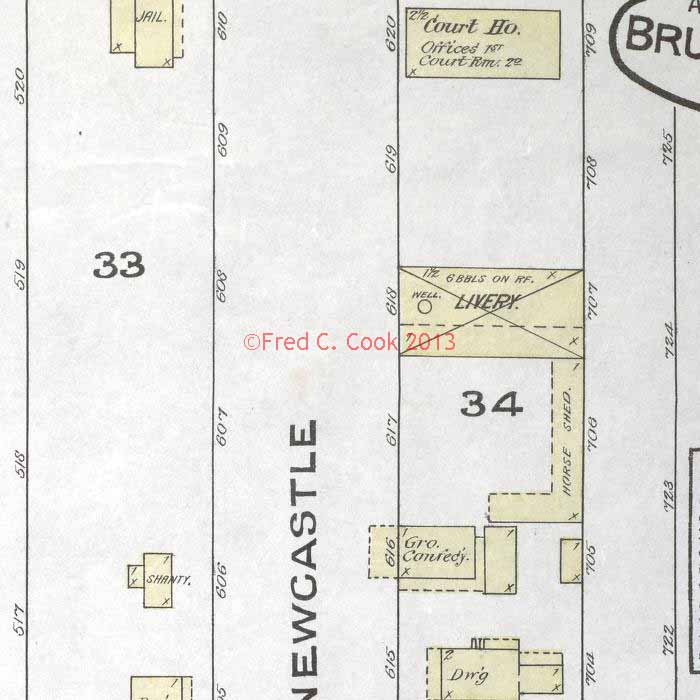

The same directory identifies the “beer and mineral water

department” at 202 Bay Street (see map on page 41). This

location was the company’s distribution office. Since this

firm’s main business was brewing, it will be discussed in detail in

Chapter Five with reference to their extensive works on Albany

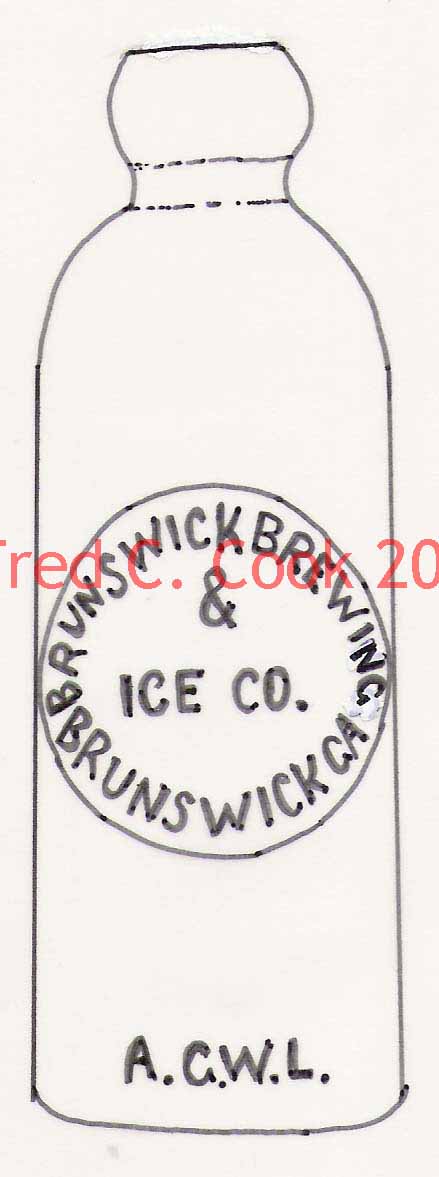

Street. Shown below is the only type of soda bottle embossed

with the company’s name:

S103.1

Aqua/ tooled top/soda/ Hutchinson Stopper

Height- 6 ¾”

Diameter- 2 11/32”

pg. 20 |

|

pg. 21

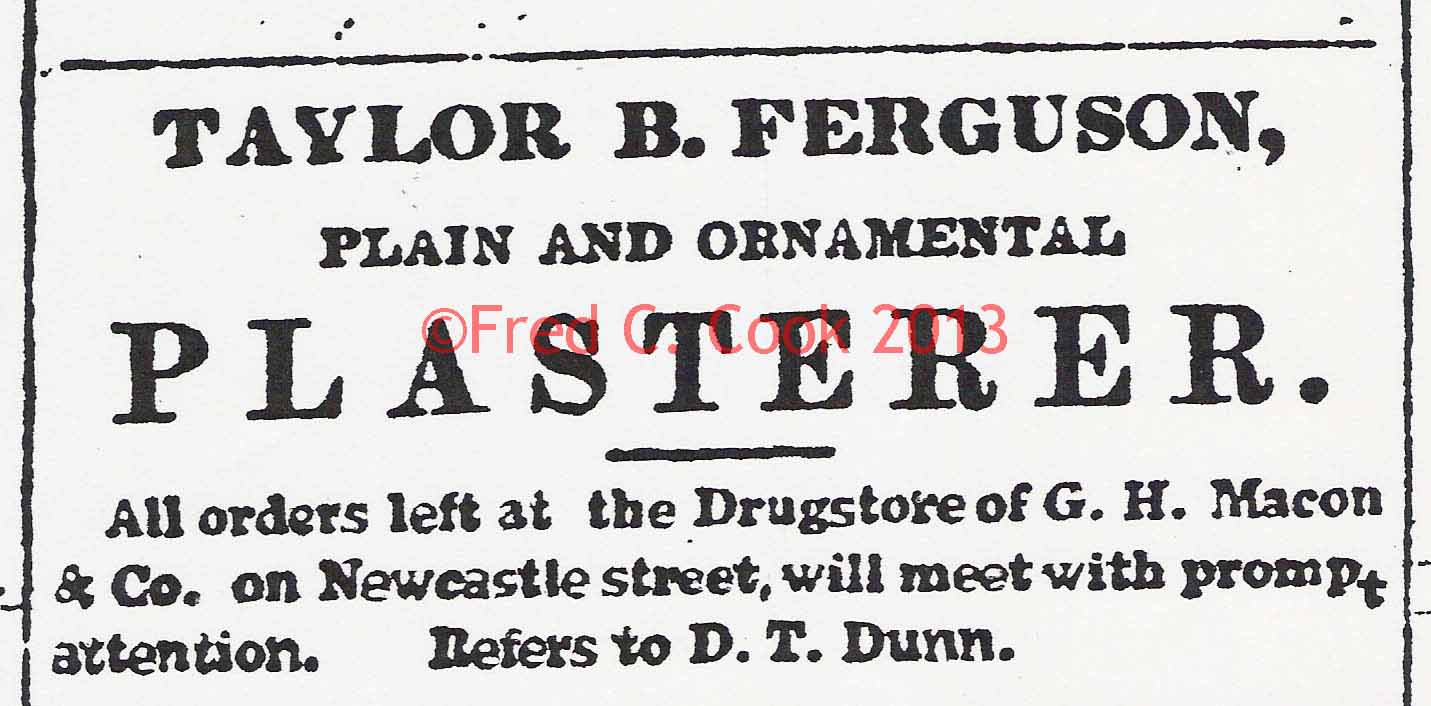

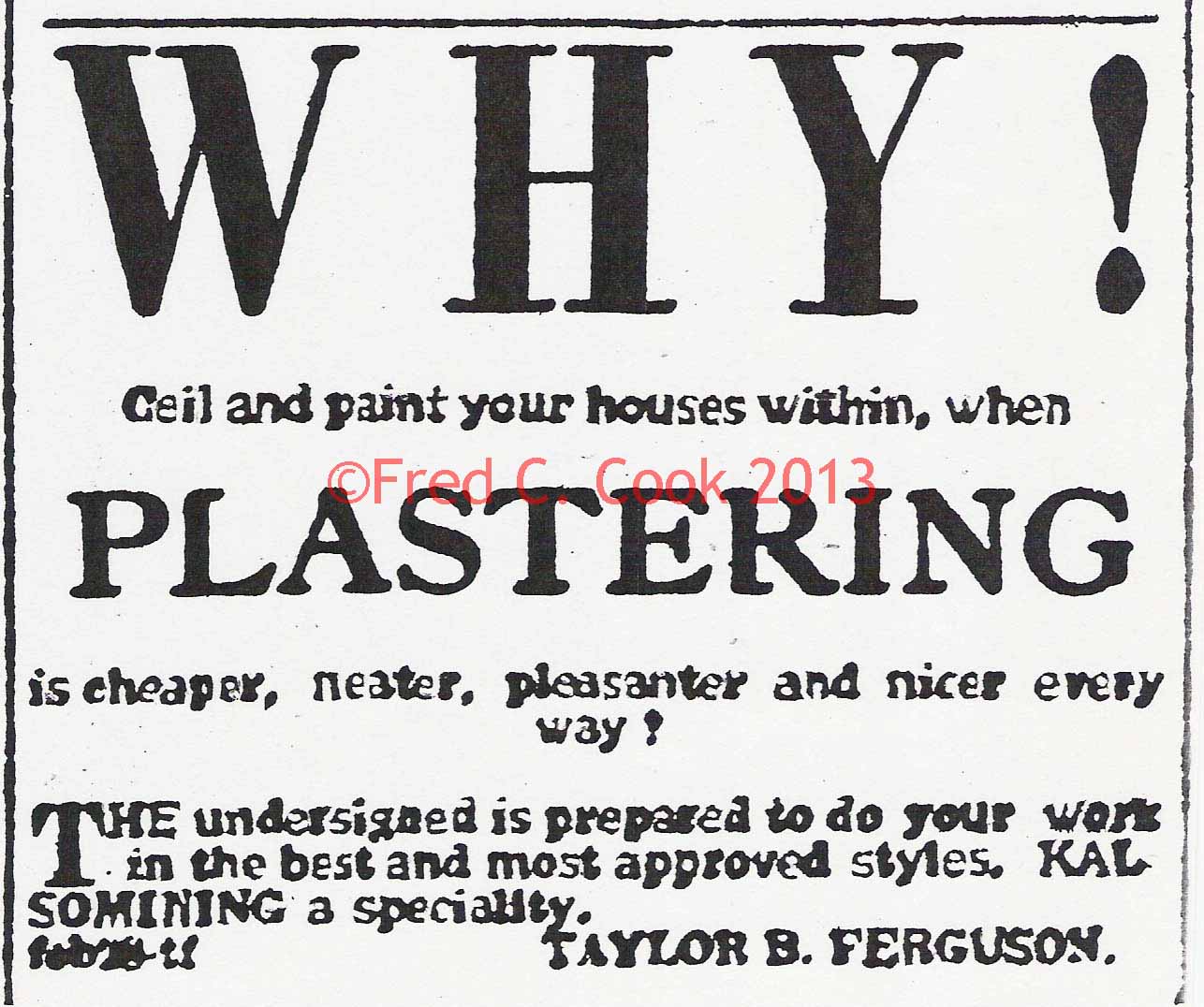

T.B. Ferguson (Taylor Butler Ferguson)

was a Civil War veteran who served in Company C of the 5th

Georgia Infantry. His unit was formed in Richmond County,

Georgia. Since the US Census reports his place of birth as

South Carolina, it is likely that he was from the western region of

the state near Augusta.

After the war, Taylor moved to Brunswick and worked as a

plastering contractor. The following note was published in the

personal mention section of The Brunswick Daily Advertiser-Appeal

on August 2, 1876:

“Mr. T.B. Ferguson is putting on the finishing touches to

the Moore & McCray store. It is an imitation of granite, and

is certainly very neat.”

In 1880 Taylor married “Mattie” (Martha

Lambright). The Ferguson couple became the parents

of five girls and one boy.

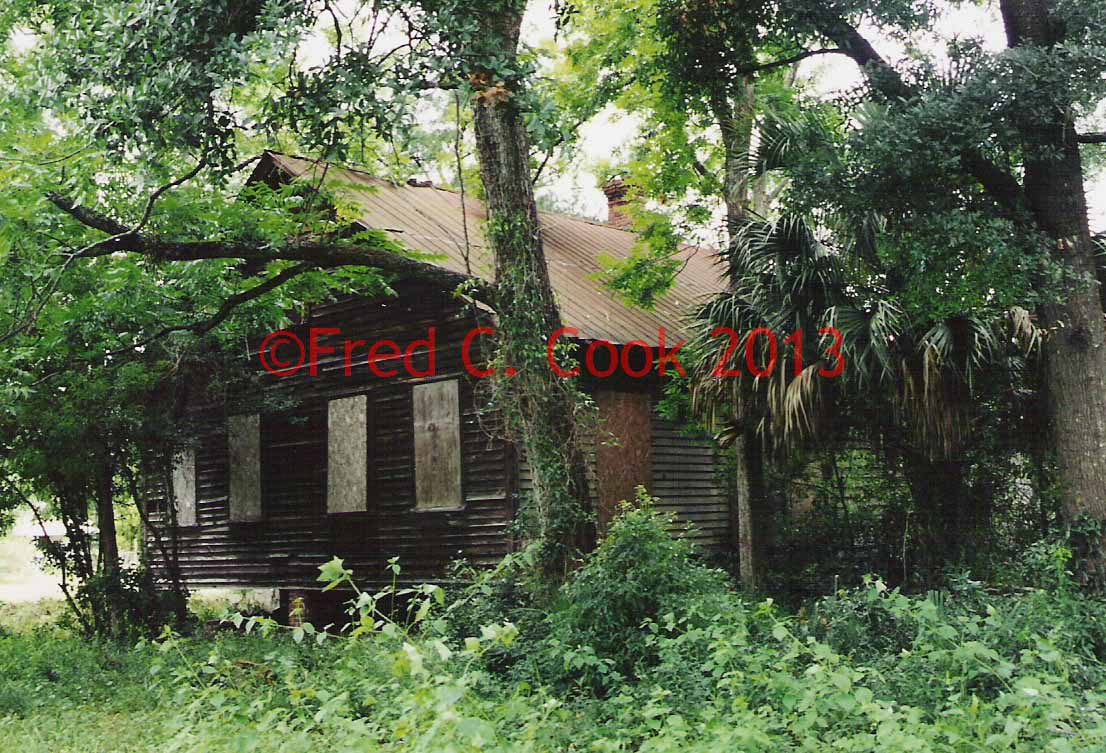

By 1890 the Fergusons had built a comfortable home at 618

Cochran Avenue in the Brunswick suburb called “Dixville.” The

Ferguson home was a high gabled wood framed structure with

wide front and back porches.

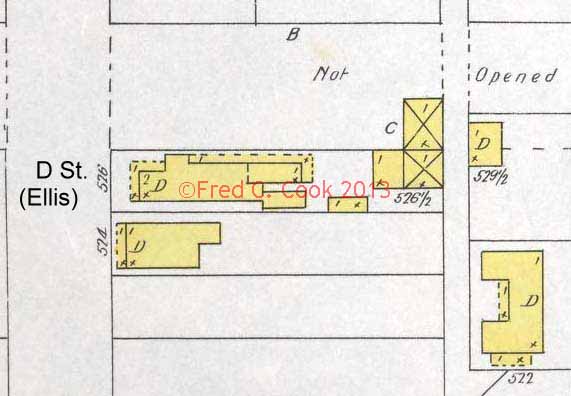

The historic property map of the house shown on

page 22 suggests that the

original back porch had been enclosed and a rectangular extension

added sometime before 1910. These modifications were probably

made as the Ferguson family grew. Twin chimneys served

four fireplaces, one located in each of the house’s big rooms.

In spite of its solid construction, local authorities condemned the

Ferguson home and ordered it to be demolished in September,

2001.

The Brunswick Advertiser-Appeal December

13, 1876

The Brunswick Advertiser-Appeal April 10,

1880

pg. 21 |

|

pg. 22

It is indeed fortunate that photographs of the house were made

before its destruction. The study of the Ferguson

family history was supplemented by excavations in the back lots of

616 and 618 Cochran Avenue.

Rear view of the Ferguson home and bottling

plant. Photo taken in 2001.

Note back porch, “bottling room” and rectangular extension have been

removed.

Recorded Jan 5th

1892

Edwin Brobston

Deputy Clerk

State

of Georgia

County of Glynn

$72000 Brunswick January 6th 1892

For value received to wit. One soda

water fixture for the manufacture and bottling of soda water

one lot of bottles one lot of siphons and one horse and wagon

and one harness. I promise to pay to the order of James

E. Lambright Seven Hundred and twenty ( 72000

) Dollars, The said amount to be paid in forty eight monthly

payments of fifteen dollars per month until the full amount is

paid

pg. 22 |

|

pg. 23

Commencing on the

first day of March 1892 and do hereby create a lien on the

above described property in favor of the said James E.

Lambright until this note is paid in full.

witness

J Michelson

Taylor B. Ferguson

L J Leavy Notary Public Glynn Co Ga

Taylor borrowed the 720 dollars necessary to begin his soda

water business, free of interest, from his father-in-law James

Edwin Lambright, who served as local justice of the

peace, with office at 508 Monk Street.

A small scale soda business seems to have been a risky venture

considering the overwhelming competition of Brunswick Brewing & Ice

Company, which was only 7 blocks south of Taylor’s business.

Manufacturing soda water may have been a part time endeavor for him,

but the local directories from 1892 through 1901-02, list Taylor

only under the description of “soda water manufacturer”. He

probably operated his business from the small room he created by

enclosing a portion of the old back porch at 618 Cochran Avenue.

However, the 1898 city directory indicates that for some time he

used the small wood framed house next door at 816 Cochran Avenue as

a business location. Excavations in the back yard of the lot

at 816 produced 10 refuse pits. Taylor had disposed of

several thousand bottles in these pits, most of which were broken

(see the Ferguson property map on page 26).

Cross section of the northern most of Taylor

Ferguson’s

bottle refuse pits behind 816 Cochran Avenue.

A four foot by four foot wood lined pit privy into which Taylor

had routed a sink drain line and a barrel privy were also found

there. The square privy contained several

pg. 23 |

|

pg. 24

bottles and a large mass of oyster shells, while

only a monkey wrench was found in the barrel privy. Three

privy pits were found behind the Ferguson home, but none of

these contained any bottles. A wood burning stove was found in

one of the privy pits. In contrast to the privies another nine

refuse pits were found in vacant lots to the south of the

Ferguson home and these also contained hundreds of bottles.

All of the refuse pits south of the Ferguson’s house were in

two lots that were not owned by the Fergusons.

Taylor dug these pits close to property lines. Their

placement suggests that he did not want them to be discovered in the

event that anyone should disturb the ground during new house

construction. Most of the bottles from the nineteen refuse

pits found on the three lots were blob top soda water containers.

A small minority of the bottles were seltzer siphons, imported round

bottom ginger ale, Woolf’s disinfectant (chlorine bleach), and plain

un-embossed quart sized syrup or sulfuric acid (see Chapter One)

bottles. One bottle contained solid lime, a chemical often

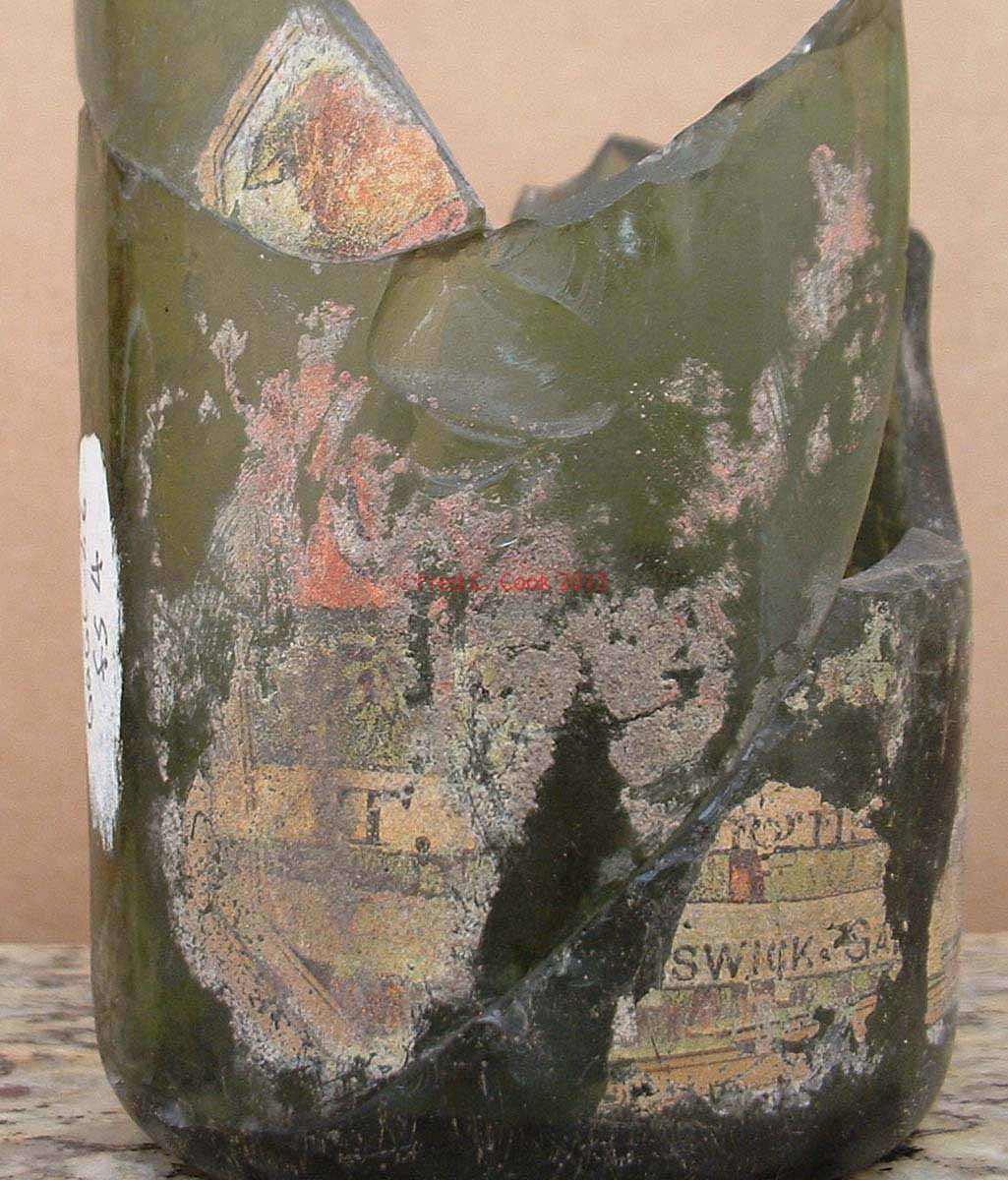

used to sweeten or purify water. A broken olive green wine

bottle with a partially preserved paper label was found in one of

the refuse pits (see photos on page 25). The paper label

depicts a young girl with an apron full of apples standing in front

of an apple tree. At the bottom of the label is a wooden sign

that has T.B. Ferguson, Brunswick Georgia written on it.

The depiction of the product’s name is partly missing, but it may

translate to “Old Apple Cider.” The soda bottles found in the

refuse pits included types representing over fifty different

businesses located in a number of northern and Midwestern states, as

well as a large number of Brunswick Brewing and Ice, Oglethorpe

Bottling Works, Brunswick Bottling Works, Crosby & Smith

and local competitor Lena Markowitz bottles.

Chicago, New York, Philadelphia and other applied

blob soda bottles with Putnam wire closures

found in T.B. Ferguson’s refuse pits.

pg. 24 |

|

pg. 25

Right side view showing girl with apple tree in the

background. Letters “ER” in a red banner at the top.

View 2 showing “ T….rgus” and “swick, Ga” on a board

sign, a picture of an apple and an “O?”in a red banner.

This interprets as T.B. Ferguson

Brunswick, GA.

pg. 25 |

|

pg. 26

Map of Taylor Ferguson’s structures on

Cochran Avenue. Red figures are privies.

Blue figures are bottle refuse pits. Long straight lines are

property lines or fences.

pg. 26 |

|

pg. 27

Some of the complete or nearly complete bottles

found in T.B. Ferguson’s refuse pits.

The presence of so many local bottles in the refuse pits seemed

unusual until the following document was found in the Glynn County

Records:

Book P. P. page 690

State of Georgia

County of Glynn,

Know all men by these

presents, that we, The Artesian Ice and Manufacturing Company, a

corporation under the laws of the State of Georgia, with our chief

office at Brunswick, in said State and county, do hereby for and in

Consideration of the sum of Twenty-five Dollars, ($ 2500

) Cash to us in hand paid, at and before the sealing and delivery of

these presents, the receipt whereof is hereby acknowledged, sell and

convey unto Taylor B. Ferguson,

pg. 27 |

|

pg. 28

of Glynn County, Georgia all

our right, title, interest, claim and demand of every character,

both in law and equity, of, in and to all of

those glass bottles of various sizes and dimensions with the cases

made for holding same, all of which formerly belonged to the

Brunswick Brewing & Ice company, a corporation under the laws

of the State of Georgia, and which were by the Receiver thereof, J.L.

Beach under the order and decree of Glynn Superior Court, sold, with

other property unto W.E. Cay, Trustee, for certain persons, and

afterwards by said bidders their said bid and interest was

transformed for value unto The Artesian Ice & Manufacturing Company,

and said Receiver directed to execute title to said corporation

aforesaid, which deed said Receiver duly executed and delivered on

December 1st 1895, and the said bottles being identified

by the stamps “The Brunswick Bottling Works”

blown on bottles, likewise all of those bottles with the words

“Oglethorpe Bottling Works,” blown thereon, and as well all those

other bottles with the words, “The Brunswick Brewing & Ice Company”

blown thereon, the quantity of said bottles not being capable of

specific enumeration but containing fifty gross, more or less…..

So in 1897 Taylor purchased the 7,200 (fifty gross-

see page

60) soda bottles formerly owned by Brunswick Brewing & Ice Company

for the grand total of $25.00 or about 1/3 of a cent per bottle.

Although they are not mentioned here, it is quite likely that this

lot of bottles also included those embossed “Crosby &

Smith”. With such a small investment Taylor could

afford to be careless with them. Bottles that had minor damage

or a defective rubber seal were expendable. It also seems

likely that local competitor Lena Markowitz’s bottles,

put accidentally put into Taylor’s wooden crates at the local

stores, were also expediently discarded. In addition to the

aforementioned bottles, Taylor acquired, perhaps from local

grocers and/or the consumers themselves, a large number of round

bottom “torpedo” bottles. As mentioned above, he refitted

these bottles with the more effective American made Putnam

iron wire bails, which were in common use on soda bottles after

1859. Taylor probably used these bottles for his ginger

ale and/or birch beer. The photo below shows the items found

in a privy across the railroad tracks from Taylor Ferguson’s

house. Note Taylor’s refitted “ballast bottles” with

the rusted remains of Putnam wire bails attached to their

necks.

pg. 28 |

|

pg. 29

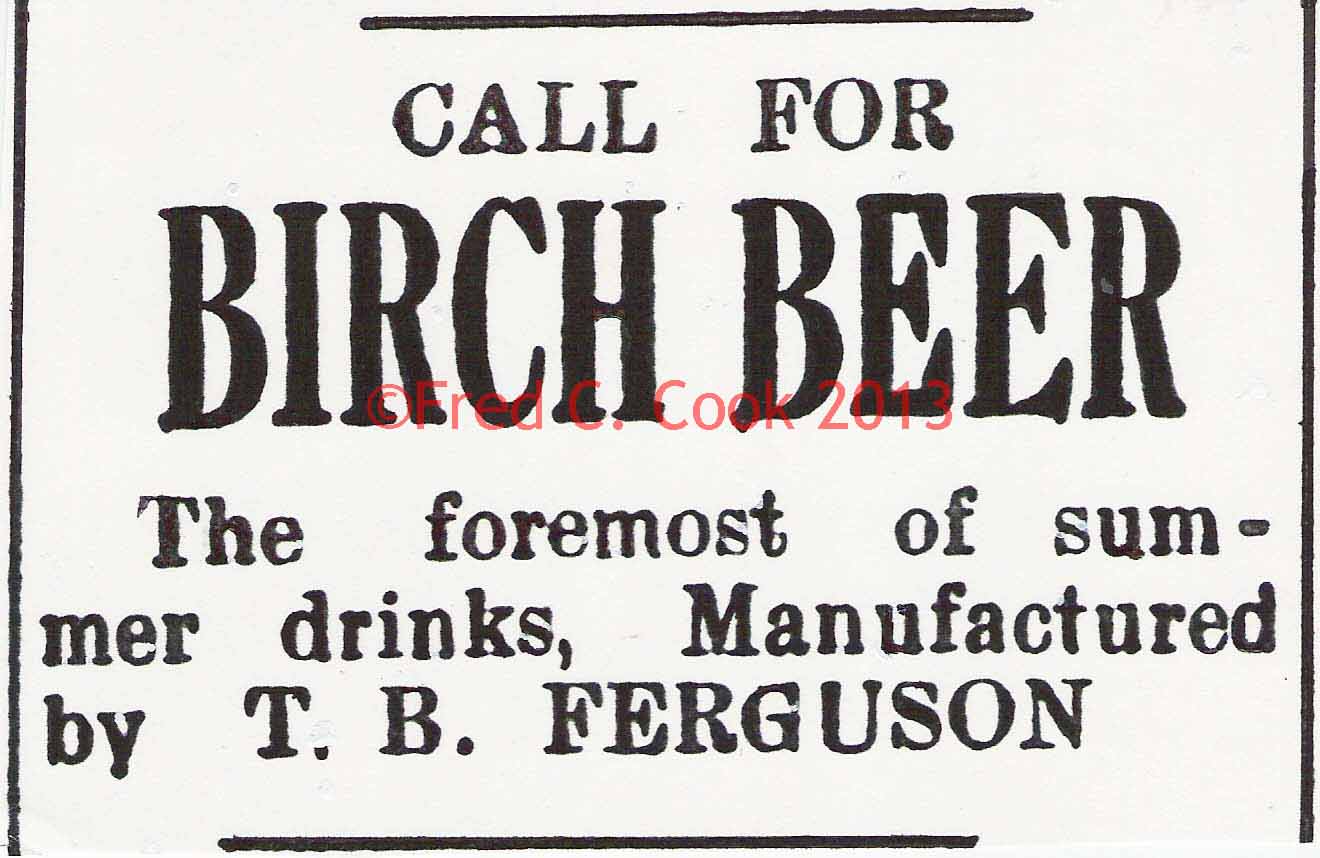

Brunswick Call June 6, 1899

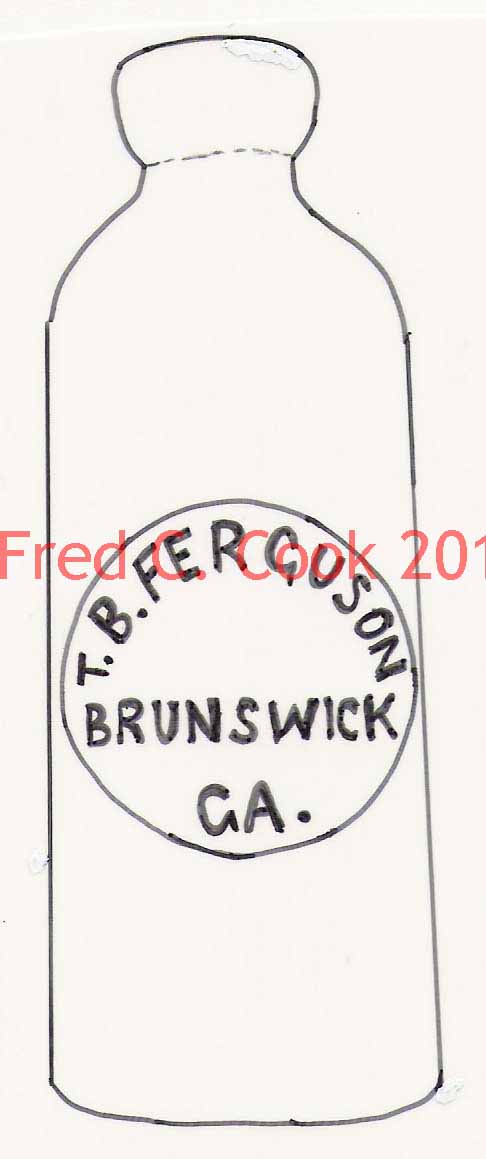

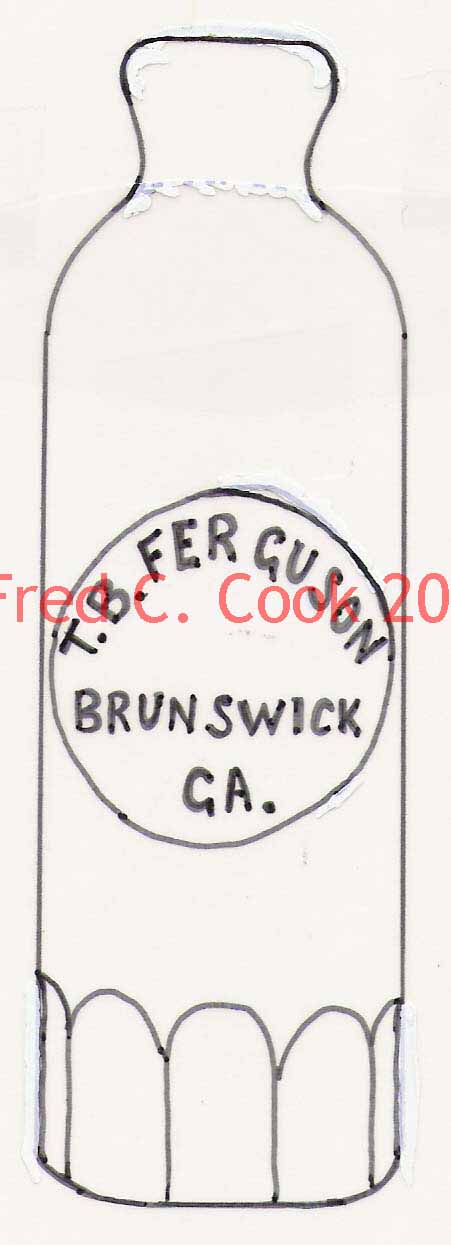

The two styles of soda bottles that bear Taylor Ferguson’s

name are shown on the following page. The taller version with

a “mug base” may have been used exclusively for birch or root beer.

pg. 29 |

|

pg. 30

S105.1 Aqua/ short/ tooled top/ soda/ Hutchinson stopper

Height- 6 5/8”

Diameter- 2 ½” |

S105.2 Aqua/ tall/ mug base/ root beer/ Hutchinson stopper

Height- 7 9/32”

Diameter- 2 3/8” |

The following advertisement, published in the Brunswick

Times Call on March 5, 1901 verifies the end of T.B.

Ferguson’s bottling business and the beginning of Louis

Ludwig’s. From 1898 until at least 1902 Louis

Ludwig owned and operated a grocery business two blocks east of

the Ferguson home.

The Ferguson family continued to live at

618 Cochran Avenue, but Taylor went back into the

construction business as a “plastering”contractor. By 1908,

the Fergusons

pg. 30 |

|

pg. 31

had moved to1324 Union Street. Taylor

Ferguson died in 1910 and was buried in the family plot in

Palmetto Cemetery, Brunswick.

Taylor Butler Ferguson and Martha

Axson Lambright Ferguson in Palmetto Cemetery.

Cast masonry urns made by plastering contractor Taylor

Ferguson.

C.O. Marlin & Company is listed in the

1892 city directory as a “manufacturer of mineral water”.

However, as mentioned above, no bottles bearing the company’s name

are known to exist. Charles Marlin and George

Hodges were the owners of C.O. Marlin

pg. 31 |

|

pg. 32

& Company. Charles Marlin was

living with George Hodges’ family at the corner of

London and Davis Streets in 1892. Their business was located

at 416 Bay Street. It is likely that they were using bottles

from George Hodges’ old Oglethorpe Bottling Works.

You will recall that George Hodges had owned and

operated a local drug store and bottling business several years

earlier. In 1890 Charles Marlin had been working

as a clerk with residence at the corner of G and E (now Norwich)

Streets. By 1896 Charles Marlin was working as a

clerk at Morris Elkan’s dry goods store on Newcastle

Street. There is no further record of C.O. Marlin &

Company and it is assumed that it went out of business shortly after

1892.

William B. Gunby was manufacturing mineral

water at his residence on the corner of G and E Streets in 1892.

Although no street address is given in the directory, the location

has an identical description as Charles Marlin’s

previous residence. It is quite possible that there was some

connection between Gunby’s business and Charles

Marlin. According to the 1892 Brunswick city Directory

William Gunby was also proprietor of a saloon located on

the southeast corner of Bay and Monk streets (300 Bay Street).

Two years earlier Gunby was working as a “dealer in real

estate” and “dealer in sewer pipe, fire brick and building material

generally.” William Gunby’s rapid and drastic

change in business interests is puzzling. No bottles embossed

with William Gunby’s name are known to exist. William

Gunby is not listed in the city directories published after 1892.

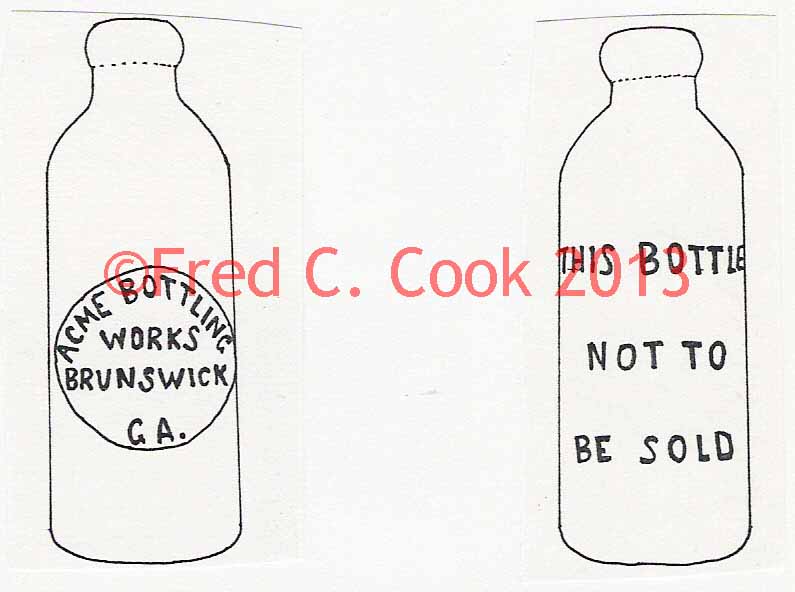

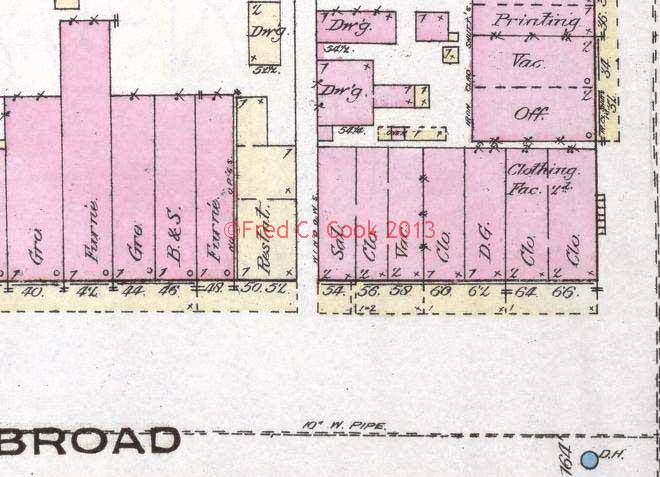

Acme Bottling Works The 1896 city

directory lists “Acme Brewing Company” as a Macon, Georgia based

business. An earlier reference to “Macon Brewing Company” was

found in the 1892 city directory. This may have been the same

company, but no bottles are known to bear Macon Brewing Company’s

name. John G. Campbell was the agent for Macon Brewing

Company at 416 Bay Street in 1892. In 1896, Richard V.

Douglas was a wine and liquor dealer located at 206 Bay Street

and the local agent for Acme Brewing Company (see map on page 40).

Richard lived at 607 E Street (Norwich), next to McKendrie

Methodist Church. A final listing for this company is in the

1905 Brunswick City Directory where its address is given as 224-226

Bay Street. This was the site of the old Ocean Hotel (see map

on page 48), which had been torn down and replaced with two brick

buildings between 1893 and 1898. The Acme bottles are of the

soda water type (see bottle on the next page) and the embossing on

them suggests soda contents; therefore the company and their bottle

design are included in the soda section of this book. No other

information pertaining to the company or their products has been

discovered.

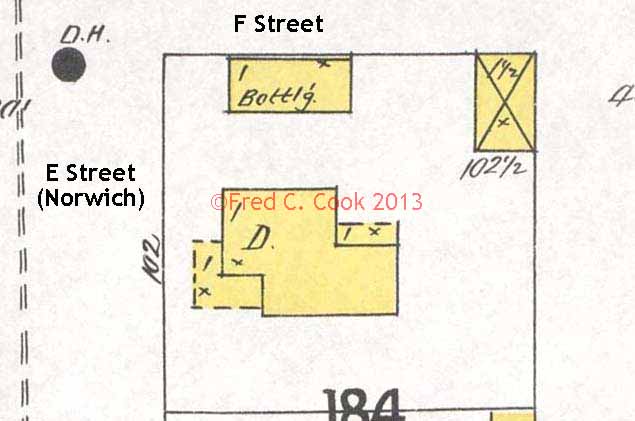

L. Markowitz does not appear in the city

directory until 1896, when she is recorded as “Mrs. L. Markowitz

grocer, S. Albany and London.” Lena and her husband

Nathan were German immigrants. Nathan, born in

1872, had immigrated to America first, arriving in 1890. He

returned to Germany to marry Lena in 1893. Nathan

and his new bride sailed to America in 1894. Jake

(Simon) Markowitz, born in 1850, who was probably Nathan’s

father, immigrated to America in 1881. He had been in

Brunswick since at least 1892 and probably encouraged the young

couple to settle there. Jake was a well know saloon

proprietor at 308 Oglethorpe Street in 1892. Nathan was

22 and Lena was 24 when they moved to Brunswick. Census

records indicate that both Lena and

pg. 32 |

|

pg. 33

S104.1 Aqua/ tooled top/ soda/ Hutchinson Stopper

Height- 6 22/32”

Diameter- 2 15/32”

Nathan could read and write English in

1900. Nathan did not waste time becoming involved in

the liquor business. The following article was published in a

local newspaper on August 12, 1894:

“Baumgartner’s

old stand, corner of Monk and Oglethorpe Streets, is being fitted up

as a Saloon. Nathan Markowitz will be its

proprietor. This will make three saloons on that corner.”

The Markowitz’s

grocery store on the corner of London and Albany streets was an “L”

shaped structure. The wing that was parallel to Albany Street

was devoted to the grocery business, while the wing that faced

London Street was used as a dwelling. The 1896 Brunswick City

Directory lists Lena as the grocery store’s owner and

Nathan as its clerk.

Although it has been modified for modern business use, the old

Markowitz structure still stands. The little red building,

shown below in a modern photo, is now an unused commercial

structure. It served as a liquor store in the last half of the

twentieth century and was know variously as “Dixon’s, the “Red Barn”

and later as the “Little Jug.”

Within two years the Markowitz family had moved to a larger

house at 102 E Street (Norwich). At this time Nathan

was manager of the family soda water business that was housed in a

15 by 30 foot building next to their home on the edge of F Street

(see map on page 34). A stable large enough to house a horse

and wagon was located in the northeast corner of the property.

It is interesting to note that all of the soda water bottles used by

the Markowitz business were embossed with Lena’s name,

L. Markowitz.

pg. 33 |

|

pg. 34

The Markowitzs continued to operate their

soda water business into the early twentieth century, at least until

1902. The fate of Nathan’s Saloon is unknown.

Sometime after 1902 the Markowitz family moved to Savannah

where in 1910 Nathan was working as a local salesman for a

Savannah biscuit company. In 1920 Nathan was operating a

gasoline station in Savannah.

Old Markowitz store on the corner of London and Albany

Streets

Markowitz home, bottling house, and stable on E Street in

1898.

pg. 34 |

|

pg. 36

CHAPTER FOUR—BRUNSWICK’S

EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY SODA BOTTLERS

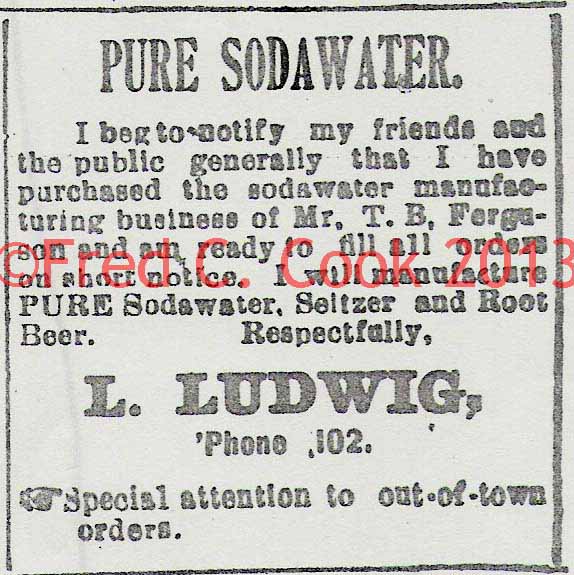

Louis Ludwig bought Taylor Ferguson’s

soda business in the spring of 1901. Louis was born in

Russia in 1864. His wife Valerie was born in 1863.

They were married in 1891 and immigrated to America in 1892.

The 1900 census indicates that they could read, write and speak the

English language. The Ludwigs did not have any

children. Louis Ludwig’s first appearance in the

city directories is in 1896 when he is listed as: “Grocer- F

Street corner Cochran”. His residence is given as the same

location. By 1898 the Ludwigs had moved their business

to the two story structure on the northwest corner of London and Lee

Streets in “Dixville”; address 1615 London Street. Since in

both directories give their residence at the same address as their

business, it is likely that the Ludwigs, like many other

local grocers, lived on the second floor, above their grocery store.

The Brunswick Call records a strange sequence of

events concerning Ludwig’s Dixville business.

Monday October 17, 1898:

Mr. L. Ludwig has sold out his grocery business on London

Street to Mr. Lazrus who will continue it. Mr.

Ludwig leaves shortly for Jacksonville where he will go into

business.

Monday October 24, 1898:

Mr. L. Ludwig has rented the store recently occupied by

C.J. Doerflinger and will open his grocery business on November

1. Mr. Ludwig will carry a large stock, the main

feature of which, will be his German delicacy department. The

CALL wishes them a success.

Louis Ludwig was back at his old Dixville location

when the 1901-1902 City Directory was published. As mentioned

above, Louis Ludwig bought T.B. Ferguson’s soda

water business in March, 1901. The location of his store was

only 2 blocks from the Ferguson’s home on Cochran Avenue.

On April 18, 1901 he upgraded the newly bought soda business with

100 siphon bottles purchased from American Soda Fountain Company of

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1902 the Ludwigs were

still manufacturing soda water at 1615 London Street. When the

next directory was published in 1905, the Ludwigs had moved

to 1200 Gloucester Street and there is no further mention of the

store on London Street. Ludwig’s business in 1905 is

listed as “bottling” and he is associated with a Mr. Cline

at 116 Richmond Street as Cline & Ludwig. In

1908 he was an Alderman on the Brunswick City Council and was living

in a nice home at 1607 Union Street. The 1910 U.S. Census

indicates he was employed by a soda water manufacturer. Two

years later he was involved with the Pepsi Cola business at 1410

Oglethorpe Street. In 1920 Louis worked as Brunswick

City Treasurer. The bottles that bear Louis Ludwig’s

name are shown on the next page.

pg. 36 |

|

pg. 37

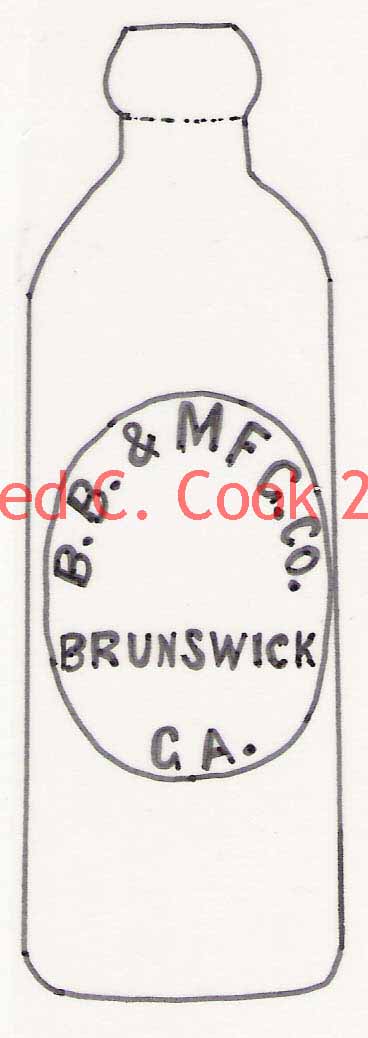

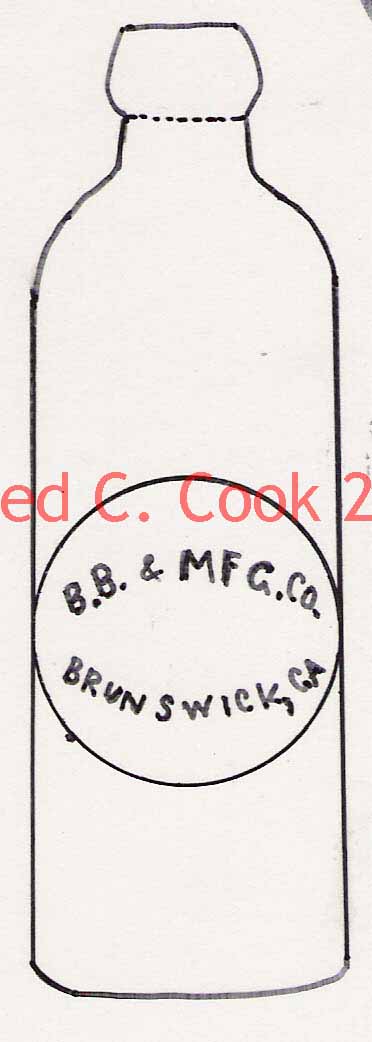

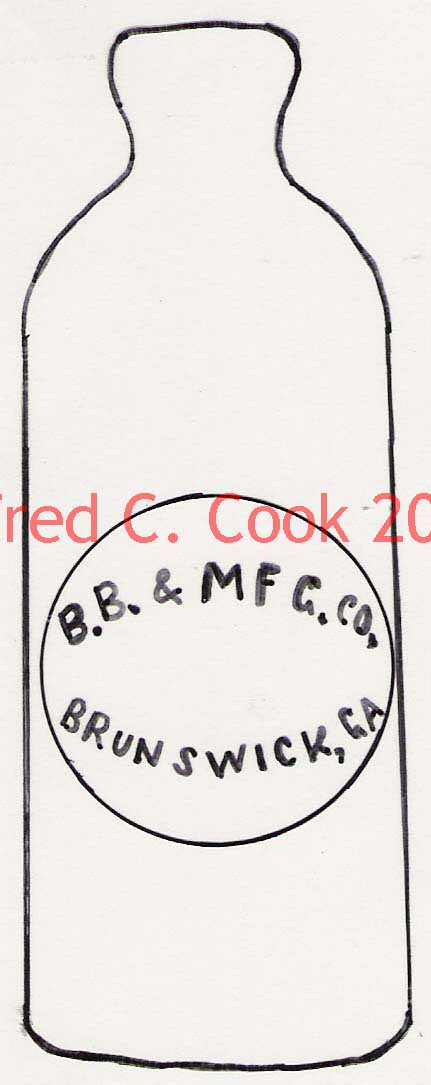

Brunswick Bottling & Manufacturing Company

appears in the city directory for the first time in 1905. It

was located at 1416 Oglethorpe Street. It is also listed in

the 1908 city directory but not in the 1912 edition. No other

information was found for this company.

pg. 37 |

|

pg. 38

S109.1 Clear/ aqua/ tooled top/ soda/

Hutchinson stopper

Height- 7 1/8”

Diameter- 2 ¼” |

S109.2 Clear/ tooled top

Hutchinson stopper

Height- 7 1/8”

Diameter – 2 ¼” |

S109.3 Clear/ short/ tooled top/ soda/

Hutchinson stopper

Height- 6 9/16”

Diameter- 2 7/16” |

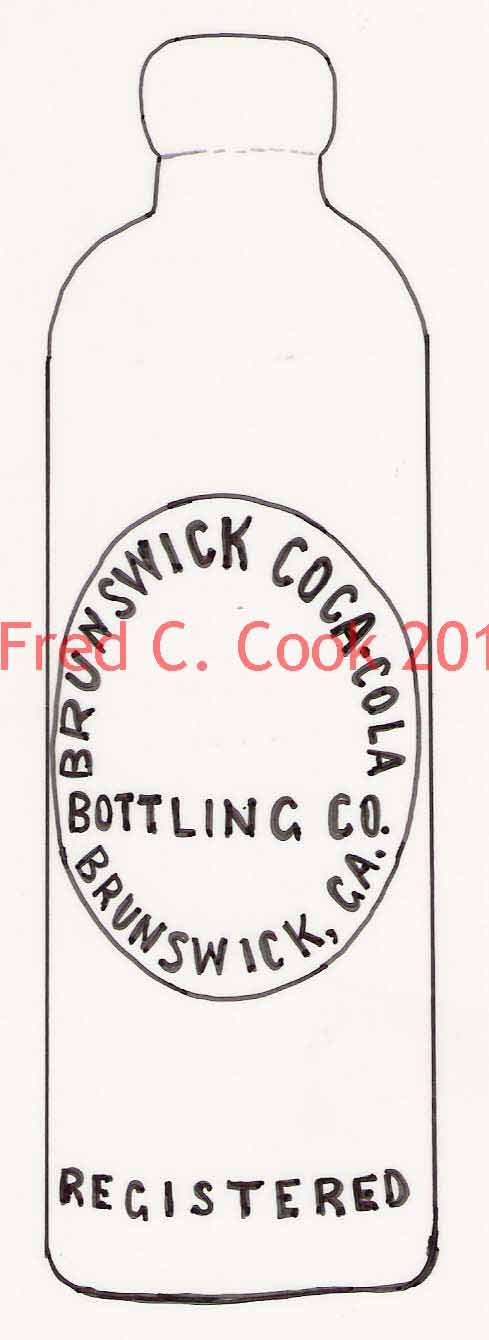

Brunswick Coca-Cola Bottling Company—1905-present.

This company does not appear in the Brunswick City Directory until

1905. Most of the company’s Hutchinson bottles show little sign of

wear. Because their condition suggests that they were not used for

long, they were probably quickly replaced with crown top bottles.

S110.1 Aqua/ tooled top/ soda/

Hutchinson stopper.

Height- 7 13/16”

Diameter- 2 3/8”

pg. 38 |

|

pg. 39

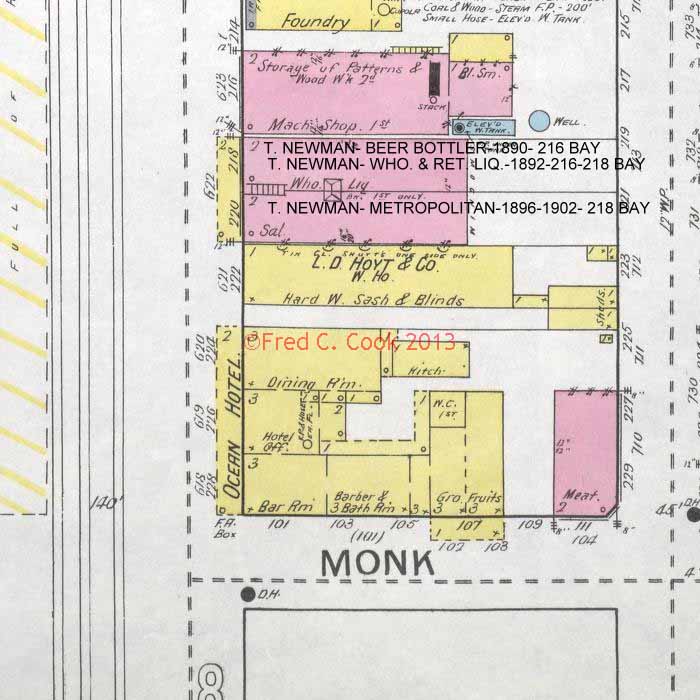

CHAPTER FIVE—BRUNSWICK’S NINETEENTH

CENTURY BEER BOTTLERS

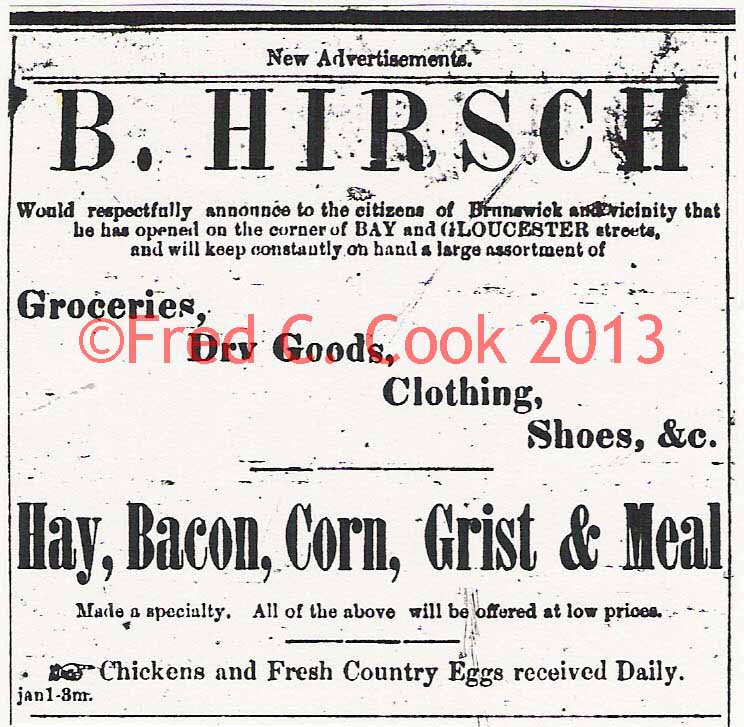

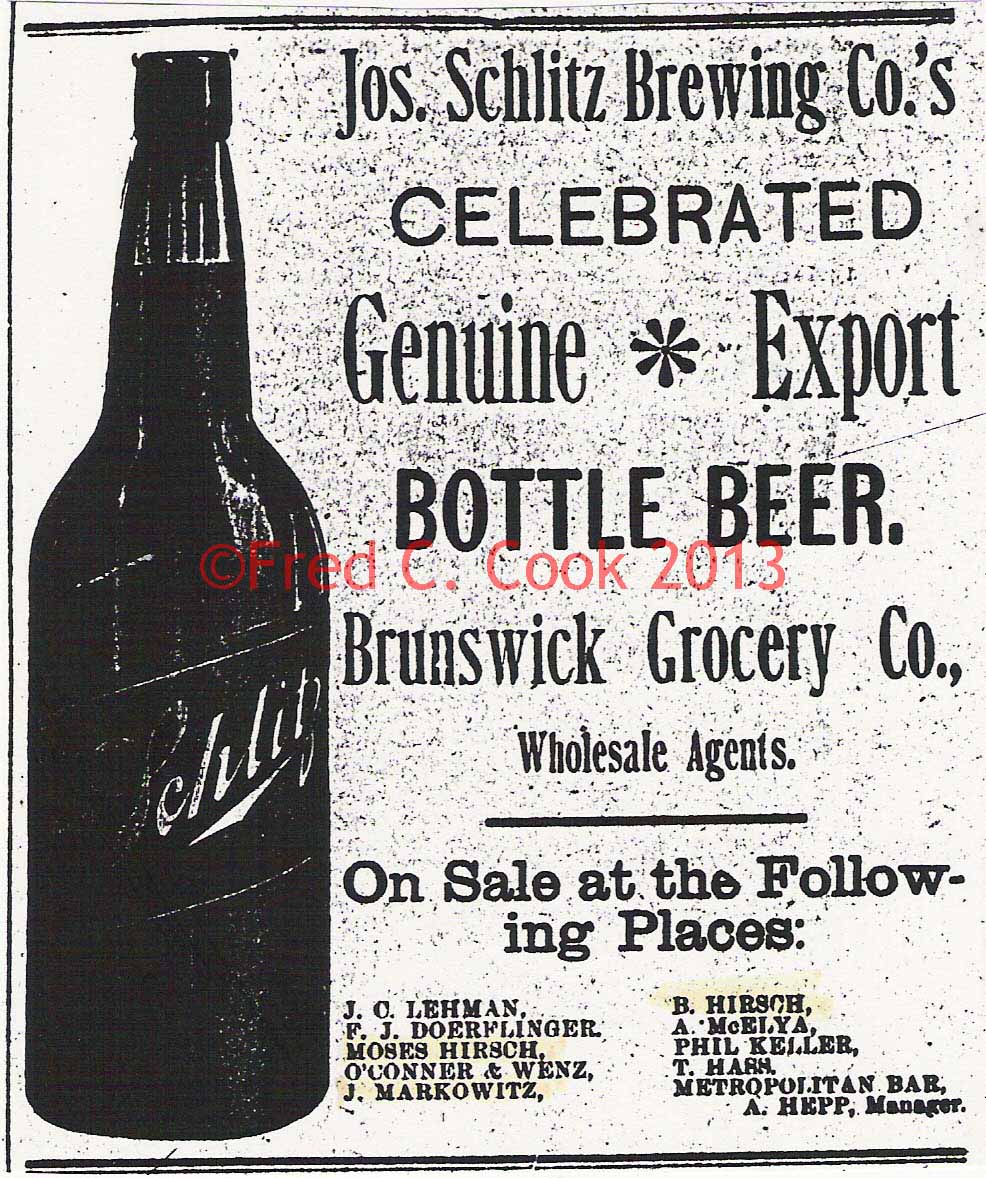

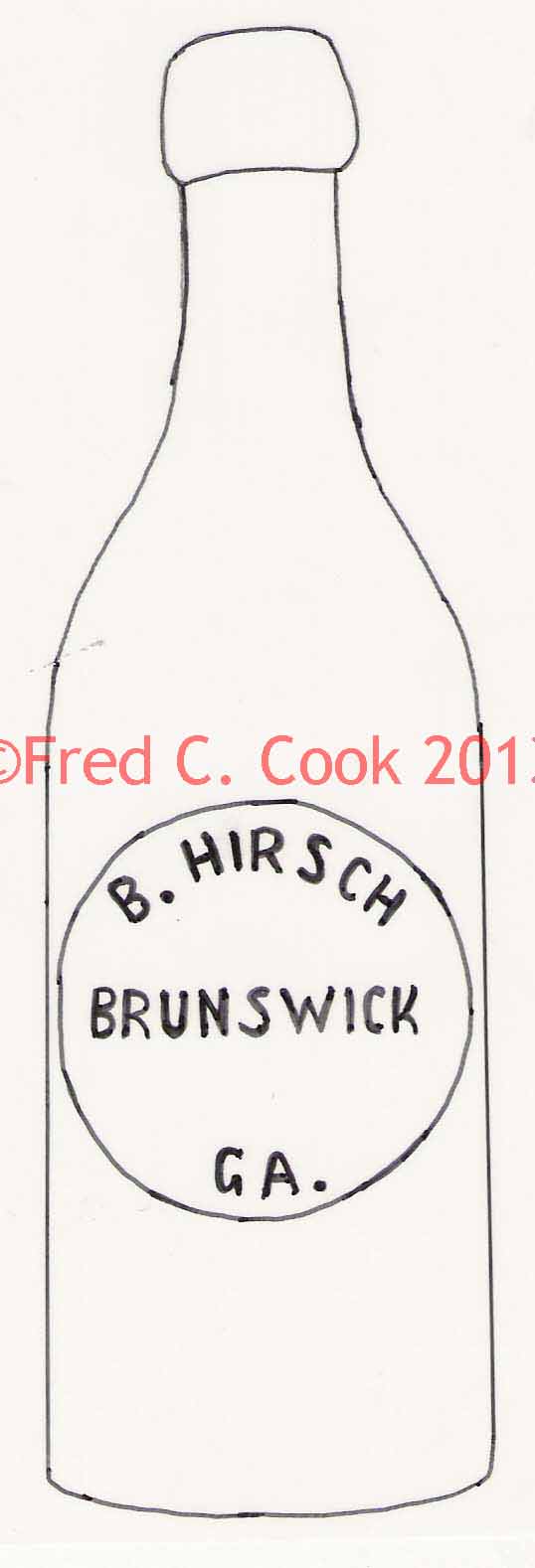

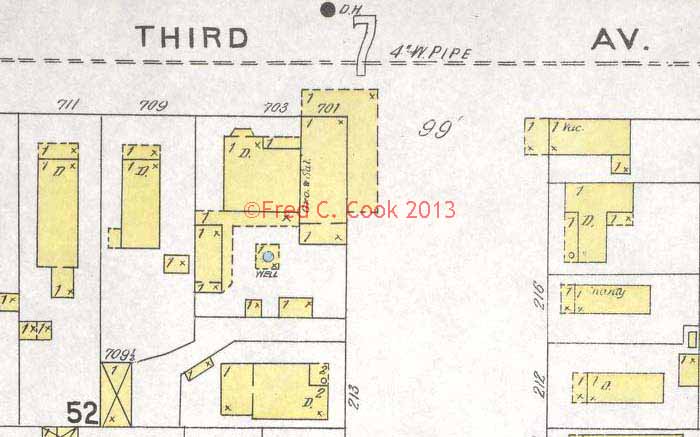

Benjamin Hirsch was born in Darmstadt, Germany in